SUCCESS, AND SACRIFICING-DECISIONS IN THE FIELD

BREAKING THE RULES FOR A POSITIVE OUTCOME

I think the most courageous question to ask anybody of authority is “What is the stupidest thing I am asking you to comply with?” I think if you are honest about wanting to listen to the answer, you will learn a lot about work as imagined versus work as done.

Keynote speaker Dr. Sidney Dekker explored sacrificing decisions during the virtual 16th Wildland Fire Safety Summit | 6th Human Dimensions of Wildland Fire Conference in May. Dekker introduced participants to sacrificing decisions and how, in hindsight, we might avoid second-guessing firefighters’ sacrificing decisions in the field. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Keynote speaker Dr. Sidney Dekker explored sacrificing decisions during the virtual 16th Wildland Fire Safety Summit | 6th Human Dimensions of Wildland Fire Conference in May. Dekker introduced participants to sacrificing decisions and how, in hindsight, we might avoid second-guessing firefighters’ sacrificing decisions in the field. The transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

I want to share with you some stories and experiences. All of these ideas about human performance have direct and immediate consequences to the ways we respond to human performance – is it going well, is it not going well? – and how we deal with each other as colleagues and fellow human beings in the pursuit of success.

The reason we want to talk about this is that we’re finding the progress on making human performance in safety even better has slowed over the past 20 years. There are go-to recipes that we have: 1) we make more rules, and 2) we try to stop things from going wrong.

One of the consequences of this, obviously, is that if you make more rules, if you try to stop things from going wrong, you gradually begin to clutter your system and shrink the bandwidth of human performance at the front line, squeezing it between what is allowable, and squeezing the native resilience from the front-line people.

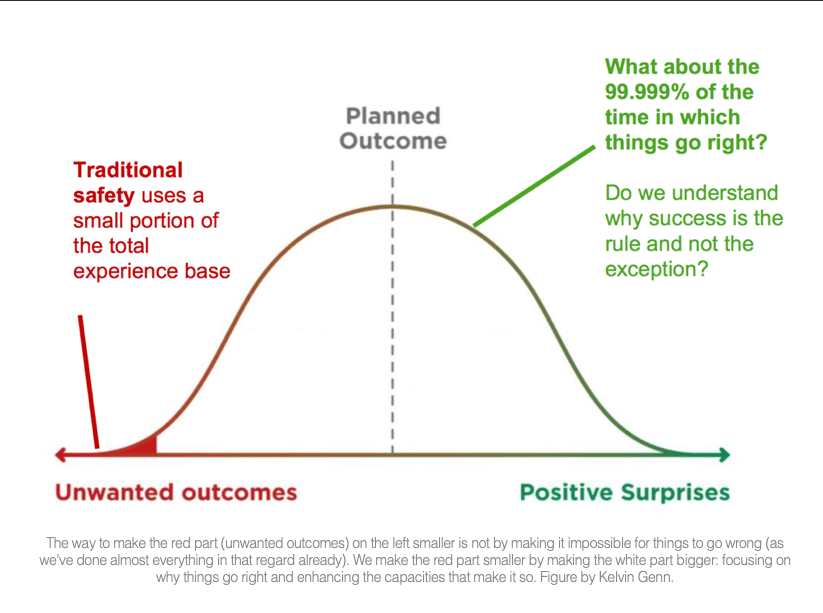

Graphic by Kelvin Genn.

Back in 2012, a colleague made this essential point: we try to understand safety by looking at non-safety. We focus on the tail end of distribution of normal work (Figure 1), and sometimes, things go wildly good on the tail end of distribution of normal work, [for example,] the Hudson River landing. It turns out, actually, that you can learn very little from these heroic recoveries because the circumstances that led to them are so incredibly unique that it’s difficult to tease out lessons from them.

We were talking to an obstetrician, and she said when it comes to performance and safety, it is as if you are trying to understand how to have a happy and healthy marriage for the rest of your days by studying a few cases of divorce and domestic violence. You study those and then you assume you know everything there is to know about how to have a happy, healthy marriage for the rest of your life. Nonsense; that’s an absolute absurd, bizarre presumption.

For the last 10 years, the safety community has said the way to look at this is to stop this obsession with squeezing the last little red bit (Figure 1) out of our human performance distribution.

In a complex world, things are not going to go well. But much more goes well than goes wrong.

I’m not saying it’s impossible to try to stop things from going wrong. It is ethically incumbent on us to try to stop things from going wrong. But if we only focus our entire discussion on human performance and safety on that, we get in trouble. This idea is infused by this iconic image of the Swiss cheese model (Figure 2) – that you want to protect a person or the thing from harm by putting all kinds of things in between. But this type of thinking is porous like Swiss cheese, and is known as the Swiss cheese model of accident causation.

Here’s an example. A hospital decided it wanted to prevent a recurring problem – a nurse dispensing medication who was constantly interrupted, therefore creating risk of dispending the wrong medication. This hospital decided – like much of health care, which seems wedded to this 30-year model of problem solving – to put a high-visibility vest on the nurse. Now, on the vest it says DRUG ROUNDS IN PROGRESS – DO NOT DISTURB, in other words, bugger off, leave me alone, solve your own problems.

My student comes back to the lab with results and says [he is] very confused. (Well, PhD students are always confused. That’s nothing new!) The nurse who wears the vest gets interrupted more. Intuitively, it makes sense – you put a high-visibility vest on the nurse and the nurse is more visible. Nurses are always in low supply and high demand. This example is just to show that unleashing this linear model of stopping things from going wrong in a complex environment actually generates results that are counter to the whole intention to begin with. And that goes for you guys. The kind of work you do takes place in incredibly complex, highly emergent situations, where it’s very difficult to predict what’s going to happen, where you have novelty and surprise, and those worlds are not made for Swiss-cheese thinking, for barrier thinking, they are made for “Oh we’ve got to stop bad things from happening,” because you don’t know what’s going to happen. So instead of stopping the bad things from happening, how do we increase the capacity for people to make good things happen?

Here is an example of a sacrificing decision [imagine a photo of a road crew member running across a busy highway with cars going 60 mph or more!]. This gentleman in the Netherlands is running across the road to peel off the masking from a speed sign because they are done with roadwork. Normally, that is supposed to happen within a whole system that guides traffic around, and cleaning up the site. The problem was that within the planning, it fell between cracks and the people who were supposed to do the traffic management were two hours and 15 minutes late. So this crew said, well we are out of time, we have to go to the next site, so they called their boss and said we’re out of time, is it OK if we just run across and pull off the tape? And he said yeah, yeah. Sacrificing decision, right? You sacrifice one goal in order to achieve another. The guys are thinking, there is daylight, the cars are still 100 yards away (even though they’re going quite fast!), so what’s the problem?

Sacrificing decisions are quite common. Where do they come from? Goal conflict, multiple goals at the same time to be achieved by all people in the field, and yet they cannot all be achieved without something giving. So there is a constant negotiation that has to go on. That’s where sacrificing decisions come from. When we face these things, it is so easy to stand back and say, “Look, how could you be so stupid? You should have waited. Two hours and 15 minutes? It’s clearly unsafe. You should’ve waited for the troops to come.” If you want to have any understanding of human performance, you need to put yourself in the other person’s shoes . . .

I was chatting to [someone] recently and the question came up, is it that people make poor choices or that they have poor choices? If they have poor choices, then we really need to look for the responsibility for that, deeper in the organization, which is of course consistent with the idea of understanding human error. It’s not that they make poor choices, it’s that they only have poor choices . . .

If you are a Boy Scout and follow the rules to the letter, you won’t get any work done. Things have to give. Some sacrifices matter. Some sacrifices don’t . . .

[Safety researcher] Jens Rasmussen said the sacrificing decisions come from this interplay between having to be faster, better and cheaper all at the same time. Now, these might not be the three goals that bound this space of human performance . . . but the idea behind this is the operating point at which human performance gets pushed around by having to be faster and better and cheaper, and you can’t be cheap and fast and better all at the same time. If you’re faster and cheaper you won’t be better or safer, for example. So, something has to give in the real world, because we live under resource constraint and goal conflict, in a complex universe. If you’re making sacrificing decisions, you’re making them in a situation that’s dynamic.

Now you might say hang on, are our rules not relevant? The scientific answer is, it depends. On what? On a lot of things. [Rene] Amalberti, [who wrote the book Navigating Safety, Necessary Compromises and Trade-Offs – Theory and Practice] did great work on this in relation to rules and safety. If you are engaged in a [very dangerous] activity where you kill or intentionally maim a member of that activity, then more rules actually do make a difference. For example, if you think about the line to the summit of Mount Everest, one of every 50 [climbers] will die. If you make more rules, you can prevent some of those deaths . . .

It’s not that rules are bad, but it depends on the context of the safety level of the activity. In wildland fire fighting, the safety exposure waxes and wanes. It’s important to think about how to shrink the bandwidth of human performance by rulemaking. One of the key phrases in thinking differently about safety is freedom in a frame. Yes, we need rules. But we have done this before. We know how you die, so let’s not do that. That’s the frame. But within that, there needs to be some freedom. The context determines the applicability of the rule.

It’s important to understand work as imagined versus work as done. Work as imagined happens in a universe that is linear, predictable, closed, no surprises, in a world that is not rapidly developing, or unfolding, or emerging. Work as imagined is linear, foreseeable, it’s what we think should happen. Of course, in the real world, nothing is by the book at all. Even your actions in the world change the world in ways that may not be entirely predictable, particularly in the sort of work that you guys do . . .

In the early 20th century there was hardly any difference between work as imagined versus work as done, because the work as planned was the work that was done. It’s simple. The world is closed. There are no surprises. It’s a factory. In that sort of world that is linear, predictable, ordered, it is also utterly joyless.

Here a scenario from a research project. Two workers are putting a pipe in a sewer to stent it. My student takes a photo [while everything is being done by the book] and the project director says OK, I will wander off and go to the next team because all of this looks good. The guys go OK, the boss is gone, let’s get some stuff done – and the rules go out the window. Work as imagined versus work as done. When the boss is gone, you put the pipe in [not necessarily following the rules, but in a way that’s much more efficient]. Do you know that [the pipe] goes in two and a half times quicker this way? Two and half times quicker! That is work that is actually done. Who benefits from that? The boss! So we were working on this and thinking, what guidance do we want to give? The thing you don’t want to do is shout, “Why are you violating this rule. Who is responsible for this? What should the consequences be?” These questions are predicated on judgments and you knowing better and your infatuation with work as imagined: “This is how the world is supposed to look. Why doesn’t the world adhere to my plans?” Because it’s the real world! So, what do you ask? You ask, “Help me understand why this makes sense?” And, “What is responsible for putting you in this position? What is the constraint? What are the goals? What is not working? What is responsible? What are the factors responsible for putting you in this position? What’s not working in my plan?”

I think the most courageous question to ask anybody of supervisory authority is “What is the stupidest thing I am asking you to comply with?” I think if you are honest about wanting to listen to the answer, you will learn a lot about work as imagined versus work as done.

I saw this on the wheel well of an airplane: “To avoid serious injury don’t tell me how to do my job.” It was in the wheel well, not very visible to the rest of the world, which to me, says something about the culture of the company.

Final little story. This was in a hospital in Canada in the mid 2000s. In a hospital, one in 13 events goes wrong. One in 13 patients gets hurt or dies because of the care they get. Which for a hospital is pretty safe. But that means you get big data. We asked, have you investigated these things? Yes, they had investigated every one that goes wrong. What did you find, we asked. These are the causes: workarounds; shortcuts; violations; errors; miscalculations; people can’t find their tools; unreliable instruments. These are the sorts of things we keep finding, we were told. Well now that you know that, what are you doing about it? They put up posters, had campaigns. [In these situations,] you tell others to care more, try a little harder. But they were still stuck at one in 13.

So then we asked what would become the miracle question: “What about the other 12? Why did they go well?”

Well, we don’t know. Well, let’s find that out. How do we find out? We don’t have dead bodies. How do we investigate a non-incident? You investigate the way normal work, work as actually done. What we found after weeks of researching how work as done in the hospital, for the 12 that went well, all the same things that happened in the bad outcomes also happened in the good outcomes. All the things that went well happened because of guidelines – 600 policies every day. Tell me about some of these policies, we asked. But they were done after two or three and then they don’t know anymore; so are there are 597 other policies are hidden in the fog somewhere? They have no idea. How can you follow them if you don’t even know them?

So it’s not surprising. We owed the people in this hospital an explanation for the difference between the 12 that went well and the one that went wrong. When we started looking deeper at the data, we found in the 12 that go well, more diversity in the team, and even the possibility of dissent. They keep a discussion of risk alive. Past success is not taken as a guarantee of success now.

In the dynamic world, past results are no guarantee. We find the ability to say “stop” well distributed throughout the team, and independent of hierarchy and rank, and deference to expertise. Don’t ask the boss. Ask the person who knows. In a professional organization, sometimes the boss and the person who knows are different people. Don’t wait for inspections and audits to improve things, improve them yourself. Break down department barriers. And we found pride of workmanship . . . It is these capacities that account for successful outcomes. If we can think about human performance and sacrificing decisions, in these capacities of making things go well, then there is progress.

Progress doesn’t sit in squashing the bandwidth of human performance even more. Progress doesn’t rest in being judgmental about things that have gone wrong. Progress about human performance and safety sits in our understanding and capabilities to enhance these positive capacities.

firefighters make sacrificing decisions, managers should think twice about challenging their actions and instead determine what circumstances led to the actions