In the wake of questions about the future of the Joint Fire Science program and the release of Canada’s new Blueprint on Wildland Fire Science, Eric Kennedy offers a set of conversation-starting ideas for the future of wildfire science. He suggests that wildland fire science is at a crossroads: rather than simply looking to preserve current funding, we need to reinvent our “social contract” with society.

This series was inspired and inaugurated in part by panel from the Human Dimensions conference in December 2018. Part 1 was published in the April 2019 issue of Wildfire.

+

By Eric B. Kennedy

It’s hard to imagine a more tumultuous time for wildfire science than we’ve experienced in North America in the past few months. In the United States, March was marked by a significant slashing: news that the Joint Fire Science program, a major actor in wildland fire research since 1998, was being recommended for discontinuation in the 2020 budget. Meanwhile, Natural Resources Canada released their eagerly-awaited “Blueprint for Wildland Fire Science in Canada, 2019-2029.” The contrast has been striking, even if much uncertainty remains about what the final outcome will be in each country.

Amid the whiplash of these developments, wildfire science remains as important as ever. Pressures from every side – a changing climate, increased settlement in urban interface areas, underfunded preparedness and mitigation programs, and excess fuel loads among others – multiply to raise the stakes that firefighters and fire managers increasingly face year-round. Fire science offers many promises including fire detection and mapping with more precision than ever before, modeling smoke and fire spread to support finer-grain tactical responses, more fire-proof building materials, and more effective suppression technologies.

This brings us to a critical crossroads: a moment where wildland fire science is concurrently under existential threat, being reinvented, and is needed more desperately than ever before. In Part 2 of this series (Part 1 can be found in the April 2019 issue of Wildfire), I argue that we need to be far more courageous in our response to these pressures. In an era of hyper-polarization and accelerating pressures, we as a fire community – from frontline firefighters to seasoned academic researchers – need to come together to reimagine what wildland fire science can and should be.

Why Research at All? Science and its Social Contract.

Before we can reimagine fire science, we need to revisit its promise and perils.

In the previous issue of Wildfire, I argued that there are two misleading and untrue myths that we tell ourselves about the scientific enterprise. The first myth is that more money leads to more science (it doesn’t, or at least not in a predictable, linearly increasing way). The second myth is that science can provide answers to the biggest challenges in wildland fire management (it generally can’t, because most of these issues are actually based on competing values, risk tolerances, and visions of ideal futures).

These myths, of course, aren’t unique to wildfire science. They’re also fables that we tell ourselves about science as a whole. In my field of social studies science, we’d refer to this as the ‘social contract for science.’ Just give us more money, scientists suggest, and we’ll shower you with good outcomes like societal wealth, health, and technology. In the case of wildland fire, these ‘good outcomes’ are often related to safety: more powerful technology for fighting fires or better models that can inform our tactics, for instance.

Yet, it’s easy to see why members of the public – and perhaps politicians writing budget proposals – might question whether we have actually delivered on these goods. Despite the Joint Fire Science annual program budget increasing from $8 million in 1998 to $14 million in 2006 (before eventually falling to $3 million in 2018), the past decade of fire doesn’t suggest that this scientific investment has meaningfully reduced the impact of wildfire on our communities. Nor has the number of publications on wildfire or amount of global fire research funding resulted in any decrease in impact – rather, they both trend upwards in unison. Fires have continued to burn, exacting a massive cost on infrastructure, public health, and firefighter and public safety.

To be clear, I don’t think this perceived failure represents any lack of investment, commitment, or skill on the part of wildfire researchers. Fire science itself cannot prevent homes from burning or protect community members. Rather, it’s only when fire science is meaningfully integrated into mitigation, preparedness, and response activities that these goods can be achieved. In other words, our fundamental problem isn’t a lack of funding for wildland fire science, it’s the chasm between the silos of research, preparedness, and response.

An Incremental Approach – Better Coordination, Better Objectives?

There have been important efforts to try to close these gaps. The Canadian Blueprint for Wildland Fire Science, for instance, identifies all the right areas of attention for work going forward. A massive undertaking, the 31-member steering committee is to be commended for working through such a broad mandate and producing such a comprehensive synthesis. It identifies six themes that require ongoing scientific work:

- Fundamental physical fire science, including fire behavior models and risk assessment

- Recognizing indigenous knowledge in meaningful and collaborative ways

- Building resilient communities, including codes, standards, and WUI fire spread modeling

- Ecology, including fire impacts past, present, and future, and integration of silviculture

- Fire management, including decision support, knowledge exchange, and occupational health

- Physical, mental, social, and economic impacts, with a holistic definition of community health

The document also lays out a wide variety of suggestions for how to deliver on research in these areas, including student training, thematic working groups, the establishment of a national coordinating committee for science, and the support of conferences and virtual knowledge exchange.

Yet, there’s also potential risk. One of the exemplars identified as a “proven model … for coordination of national wildland fire science” is the Joint Fire Science Program, which currently faces an existential funding threat. In its Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Justification, the US Department of Agriculture proposes “permanently cancel[ing]” the Joint Fire Science program, arguing that the program is no longer necessary as …

“…the Forest Service will focus reducing wildland fire risk, contributing to the improvement of forest and grassland conditions across shared landscapes, and contributing to rural economic prosperity.”

The other example cited as a model was the Bushfire and Natural Hazards Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) in Australia. Yet during the panel on funding mechanisms for fire science at the Human Dimensions of Wildland Fire conference in Asheville, North Carolina in December 2018, some attendees expressed concern about the difficulties present in that structure as well. Because the CRC is funded on a relatively short-term basis given its size and scope, it creates challenges for establishing long-term projects that exceed that time horizon and for funding responsive research during the latter half of a grant period.

In other words, I wholeheartedly agree with the priorities established by the Blueprint and think that the steering committee is absolutely correct in their recommendations. Yet, I worry that such an incremental approach – slightly tweak research topics towards priority areas, lobby for more funding, and adopt a similar coordinating body to the Joint Fire Science or CRC model – has a chance of exposing Canadian fire science to the same long-term limitations and risks these organizations are currently experiencing.

A More Radical Path Forward.

To review, there are at least three challenges that we face as a wildland fire science community. First, there is arguably a perception that we might not be delivering on the outcomes we promise. Second, there’s massive volatility: one of the biggest players might be about to disappear, while even established ongoing models can be limited in their coordinating functions when hamstrung by short-term funding. And third, the wildfire challenge is poised to become worse – not better – in terms of both threat and impacts.

Given these considerations, I think we need to be more courageous and radical in our strategy going forward. In the spirit of spurring discussion – and certainly not having perfect answers – I’d offer five suggestions for how we might reinvent this enterprise from the ground up.

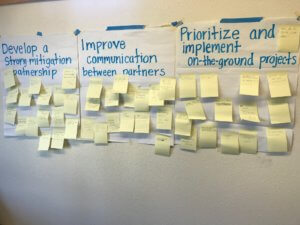

(1) We need a wholesale changing of priorities, accelerating the shift from investigator-driven research to end user- and community-motivated investigations. The impact of wildfire is simply too significant and real – in terms of lives, health, communities, and infrastructure – to allow a business-as-usual approach to fire science. Academic curiosity is an insufficient justification for investing time and funds into research, nor is there reason to believe that important topics would go unfunded in a user-needs driven model (e.g., there will still be a critical need for historical work to establish past fire regimes and effective management strategies).

In short, we need a model where users and communities are the ones in the driver seat, identifying the questions that matter to them and where research could tangibly improve outcomes. The Joint Fire Science Program indeed represents a strong attempt at shifting this equation, although making this change lasting requires engaging more broadly with incentives, norms, and structures within the academic community.

(2) We need more research coordination on an international scale. With end-users and communities identifying the questions, we then need a coordinating body that can help (a) formulate questions effectively, (b) identify existing answers, and, in the case of new questions, (c) design together teams with the right expertise to answer these questions in a meaningful way.

Team formulation should bypass traditional shortcomings of research group formation (e.g., over-emphasizing privilege and established researchers or networks) and emphasize interdisciplinary and Indigenous expertise, as well as researchers from diverse backgrounds and different career stages. This coordination needs to be international in scope, as most questions have applicability across national boundaries – and would benefit from trans-national collaborations and overcoming national silos.

(3) We need to separate coordination from funding. The prospective loss of the Joint Fire Science program would be doubly devastating. Not only would it result in a gutting of money available for fire research, but it would also destroy the critical coordinating function Joint Fire Science plays in setting priorities. Likewise, the CRC and any such Canadian creation would be similarly vulnerable to being eliminated due to a lack of funding – a move which would gut coordination and collaboration precisely at the moment it was most needed to help steer research to new funding sources.

Navigating the role of this body relative to granting councils and prospective funders would obviously be complicated (e.g., there would be no way to force funders to support these projects as opposed to lone wolf, independently driven efforts), but the credibility of user-driven, thoughtfully scoped projects could help establish a track record of success in obtaining funds from national councils, fire-specific science appropriations, and private sector opportunities (such as insurance companies).

This would also free us to lobby more effectively as a community for increased investment in fire science from all levels of government and from multiple agencies and programs, rather than letting funding be consolidated into and ‘owned’ by a single, more vulnerable program.

(4) We need to embrace “slow science.” Counterintuitively, as the wildfire threat increases, we need to respond with slower science. Among other things, the slow science movement emphasizes the value in reducing the number of projects being undertaken concurrently by researchers. It prioritizes quality over quantity, encouraging those in research to invest increased time in a smaller number of efforts.

The international coordinating body would have a key role to play in modeling this behavior, seeking to distribute funds throughout the research community rather than centralize it among ‘superstars,’ establish mentoring relationships that bring new researchers in and provide opportunities for support, and encourage teams to stay with projects through implementation, evaluation, and iterative improvement – rather than simply seeking to publish high volumes of papers. By modeling this behavior on an international scale, it would also create subject-wide support for this practice, helping to address tenure- and promotion-related concerns.

(5) We need to integrate science into preparedness and response. I imagine that most readers would agree that there is a need to reemphasize preparedness funding rather than responding to wildfire simply by a relentless increase in response spending. Likewise, we should push for research funds to be found from a new home: not from a separate line item for science, but as a component of preparedness and response. This means renegotiating that ‘social contract,’ moving from a model of “give us the money to get the goods” to “share your questions and we’ll give our capacity in partnership to answer them.” It will require engaging with federal and provincial/state governments alike, building credibility through examples of science having improved outcomes, and embracing a model where we are judged on outcomes (e.g., how our work supports fire managers) rather than outputs (e.g., the publications we write).

At the Crossroads — a Call for Radical Re-imagination of Purpose.

We face a dramatic and challenging crossroads for fire research. On one hand, our core institutions are at risk, such as the potential loss of the incredibly valuable Joint Fire Science program. On the other, we face an ever-accelerating problem that will not be adequately addressed through a ‘business-as-usual’ approach to science. To respond, we need to do more than simply ask for more money (or attempt to preserve the money we have). Rather, we need to radically reimagine our purpose as a research community by focusing on end-user driven questions, designing new institutions that span national boundaries and reduce political vulnerability, and creating a new generation of fire science that is reflective, focused, purposeful, and action-based.

For more background, read the Blueprint for Wildland Fire Science in Canada

+

About the Author

Eric Kennedy is an Assistant Professor in the Disaster and Emergency Management program at York University in Toronto, Canada.

With a Ph.D. in the Human and Social Dimensions of Science and Technology from the Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes at Arizona State University, his research focuses on how experts, agencies, and institutions manage wildfire – and deal with conflicting views on this contentious topic. He teaches courses in the ethics, sociology, and psychology of emergency management, working closely with practitioners in the field in Canada and beyond to train the next generation of emergency managers.

You can reach him at [email protected] or on Twitter at @ericbkennedy.

This is the second in his two-part series for Wildfire, exploring wildfire science, research, and funding.