By Dr. Josh Whittaker, Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC and the University of Wollongong, and Dr. Mel Taylor, Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC and Macquarie University

New South Wales, Australia faced some of the worst bushfire conditions ever forecast for the state in January and February 2017, which included the “Catastrophic Fire Danger” rating (Australia’s highest danger level for fire) for many communities. During this time, a number of large and damaging fires occurred. Fortunately, no human lives were lost during the worst of the conditions.

Following the fires, the New South Wales Rural Fire Service (NSW RFS) commissioned the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC to conduct research into preparedness and responses by communities affected by the Catastrophic Fire Danger warnings and fires.

The research involved interviews with people affected by the Currandooley, Sir Ivan and Carwoola fires, along with an online survey of residents in bushfire risk areas throughout NSW.

The Fires

The Currandooley fire was caused by a bird set alight from contact with a high-voltage powerline and subsequently landing in dry grass. Under Severe Fire Danger conditions, the fire destroyed a house, sheds and two vehicles. Approximately 200 sheep and cattle were lost.

The Sir Ivan fire ignited from lightning strikes near Leadville and burnt under Catastrophic Fire Danger conditions. 35 houses and over 50,000 hectares of land were lost. Many agricultural assets including livestock, fences, pasture and machinery were destroyed.

The Carwoola fire was caused by sparks from a metal cutting wheel under Severe Fire Danger conditions. It destroyed 11 houses around 20 km south east of Canberra.

The research involved interviews (113) with affected residents, and an online survey completed by 549 people threatened or affected by bushfires throughout NSW in 2017. Information was collected about:

- Effectiveness of warnings;

- Catastrophic Fire Danger messages;

- Information people sought out in relation to bushfires;

- Motivations for those who sought to enter fire grounds;

- Perceptions of risk;

- How people value assets and prioritise their protection;

- Influences of previous fire history or experience on decisions and actions;

- Public expectations of fire and emergency services;

- Opportunities for greater utilisation of local knowledge and participation.

What the Research Found

Information and Warnings

Most survey respondents found warnings easy to understand, up-to-date and useful.

Participants expressed a preference for highly localised information. Survey respondents most often identified the ‘Fires Near Me’ smartphone application and website as the most useful information source.

‘Fires Near Me’ was easy to understand (88 percent), useful (82 percent) and sufficiently localised (76 percent). Two-thirds of interviewees felt the information was up-to-date. Interviewees commonly expressed strong support and a high degree of satisfaction with ‘Fires Near Me’.

Landline telephone warnings were more often seen as useful when compared to SMS warnings, (78 and 67 percent), up to date (72 and 66 percent) and timely (68 and 66 percent). Nevertheless, survey respondents most often identified SMS as their preferred mode for delivery of warnings. Most people expected to receive warnings from multiple sources. However limited mobile phone coverage, particularly in the Sir Ivan and Currandooley fires, meant that some people did not receive SMS warnings.

Catastrophic Fire Danger Warnings

After the 2009 Black Saturday fires in Victoria, Australian fire danger warnings were revised and Catastrophic was introduced as the highest level of fire danger.

These conditions do not occur regularly – this was only the second time large population centres in NSW had been subject to Catastrophic Fire Danger ratings since their introduction.

88 percent of survey respondents considered Catastrophic Fire Danger warnings to be easy to understand. 83 percent found them timely and 78 percent found them useful. However, most people do not intend to leave before there is a fire on days of Catastrophic Fire Danger. Those who intend to leave will wait until there is a fire, and others intend to stay and defend. The research shows that some people may underestimate the risks to life and property if the fire danger is not Catastrophic.

Receipt of an official warning about Catastrophic Fire Danger prompted survey respondents to discuss the threat with family, friends or neighbours (63 percent) and look for information about bushfires in their area (62 percent).

Equal proportions began preparing to defend or leave (39 percent) and a smaller proportion (12 percent) left for a place of safety.

When asked what they would do next time they received a message about Catastrophic Fire Danger, 12 percent of survey respondents said they would leave before there is a fire. 4 percent said they would wait until a fire started, then leave. 27 percent reported that they would get ready to stay and defend, while nearly a quarter said they would wait for a fire before deciding what to do.

Analysis of interview data highlights that many people believe it is impractical to leave on days of Catastrophic Fire Danger before there is a fire. Many are also committed to defending, despite being aware of the increased risks to life on such days.

Interviews with people affected by the Carwoola and Currandooley fires suggests that some people underappreciate the risks to life and property on days that are not Catastrophic.

In contrast, some interviewees affected by the Sir Ivan fire did not anticipate the size or severity of the fire, despite forewarning of the Catastrophic Fire Danger they would experience. Many felt that they were prepared to respond to smaller fires, which were more common in the area, but believed there was little they could have done to prepare for a fire of the size and severity that was experienced.

How People Accessed Information

Over half (53 percent) of all survey respondents accessed information via the internet. Respondents most commonly sought information about the location of the fire (91 percent), traffic and road blocks (64 percent) and weather conditions (60 percent).

Websites most commonly included ‘Fires Near Me’ in addition to the app; the NSW RFS; Bureau of Meteorology and various Facebook pages, including local RFS and community pages.

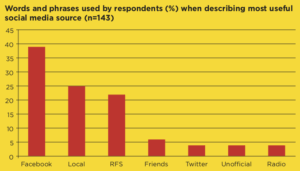

Almost two thirds (62 percent) of all survey respondents used social media during the fires.

Interviewees and survey respondents often sought information about the fire through direct observation. This is reflective of past research, where many residents left their homes and properties to go and look at the fire. For some people, observing the fire appears to have helped ready themselves to defend and, for others, confirmed the need to leave.

Perception of Risk to and Value of Agricultural Assets versus Homes

Perceptions of value and risk to agricultural and domestic assets are complex. Economic value is important in decisions about what to protect, but is balanced against utility and sentimental values. Many farm properties were large, with a wide distribution of assets. Some landholders also had additional blocks that came under threat. They often did what they could to prepare, for example by ploughing fire breaks and moving livestock, then ‘fell back’ to protect what was manageable, typically the house and nearby paddocks and sheds. This appears to have been based on an assessment of what was possible with available resources and not necessarily what was valued most.

Drivers and Motivators for Returning

Most survey respondents were at home when they found out about the bushfire (60 percent). Of those who were not at home, 71 percent indicated that they tried to return to their house or property. The drivers for returning to fire-affected areas are many, but most often revolve around the desire to protect houses and property, rescue or assist vulnerable people, and protect animals. While some interviewees complied with roadblocks, others described passing through or circumventing roadblocks in order to return. Some used backroads or gates through private property to return, sometimes on foot or in vehicles unsuitable for the roads, tracks or paddocks that were taken. There was a perception that some people were exposed to more danger than if they had passed through the roadblock.

Public Expectations of Fire Services

It is generally well understood that there are resource constraints during major fires, such as not enough fire trucks for every property. However, there is less appreciation of the operational constraints of large and dangerous fires, and that it’s often too dangerous for firefighters to directly attack the fire front.

Most interviewees affected by the Currandooley and Carwoola fires praised the efforts of firefighters and did not expect to receive personal firefighting support. Residents in Carwoola were particularly aware of the limitations from fire agencies, a message that had been clearly communicated by the local brigade over time.

Some interviewees affected by the Sir Ivan fire were more critical of the firefighting response. Criticisms centered around the perceived lack of firefighting in the agricultural areas between Leadville and Cassilis. Some saw the fire service as overly bureaucratic and risk averse.

These criticisms reflect a mismatch in expectations and should be viewed in the context of a large, destructive bushfire that burnt under Catastrophic conditions with limited operational capacity or opportunity to deal with such fires due to dangerous conditions.

Take Aways

This research is now being used by the NSW RFS to put in place new processes to better liaise with communities during major fire events, as well as to further strengthen its approach to public information through websites, smartphone applications and face-to-face communication.

The research confirms the tendency for people to wait and observe the fire directly before getting ready to defend themselves or confirm the need to leave. This behaviour presents opportunities for emergency service personnel to meet people at a time when they are seeking and receptive to information and advice.

While there is strong appreciation for the danger of fires under Catastrophic conditions, there is a need to more clearly communicate the risks posed by fires burning under non-Catastrophic conditions. Such messages could be incorporated into community education and engagement resources, as well as emergency warnings and information.

There is potential to develop additional resources to assist agricultural landholders to plan and prepare for bushfire. Resources are needed to help businesses more systematically identify assets and values, prioritise, and plan for their protection. These materials could include best practice case studies and information about insurance.

There is a need to more clearly communicate the limits of response capacity. In addition to limitations due to resource constraints, which are generally well-understood by the public, there is potential for enhanced communication about the dangers large and fast-moving fires pose to firefighters and that it can be too dangerous for direct attack on the fire front.

Findings suggest that local brigades could be effective in communicating these messages; however, this may require considerable engagement and training.

Find out more about this research at bnhcrc.com.au/publications/2017nswbushfires.

+

What was Said

“The Fires Near Me app was very good actually because I could see exactly where the fire was going and the local area and all that sort of stuff. That was good because I could see that it got out of hand, and it had jumped the highway and that’s when I knew it was gone.”

– Cassilis

“That day wasn’t even really high on my radar in terms of fire danger. It was a hot day, and there was a bit of wind, but it wasn’t Catastrophic. It wasn’t like two or three weekends prior to that when it was 45 degrees and blowing a gale. It just proves that accidents can create a big fire.”

– Carwoola

“When we came out here we knew that we had a responsibility to manage our fire risk and we did what we could to reduce the fuel load and have a good plan in place to save ourselves … we’ve sometimes found it a bit daunting about how we do all of that … we did not expect that council or the RFS would come in and save us. We believed that it was our responsibility to be aware of the risk and manage it.”

– Carwoola