FIRE & CLIMATE 2022

It’s the fuels, my friend

How a long-term fuel monitoring program in the Yellowstone ecosystem may shape our future burning

By Ron Steffens

EDITOR’S NOTE: Fire & Climate registrants can view the presentation It’s the fuels, my friend online, until October. All registered attendees for Melbourne and Pasadena can access to all presentations on PheedLoop. Registration is still open at https://inawf.memberclicks.net/fire-climate-conference-registration–pasadena.All presentations (and other past conferences) will be available to IAWF members in the fall.

When I completed my first set of sign-in paperwork as a seasonal park ranger at Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming 30 years ago, in 1992, we already knew the force of this devil.

Four years earlier, a good portion of the Yellowstone ecosystem had burned. Back then, we witnessed fire of this scale as a terror but soon enough, as forests regenerated and wildlife prospered, these fires represented natural renewal, once-in-a-few-hundred-years events.

Yet within the forest’s recovery there was a darker shadow in the smoke’s footprint, and we wondered if we would face fires in the future that burned past renewal if we’re uable to disconnect our addiction to carbon and its greenhouse gases.

In 2022, as I returned to my summer seasonal job WHERE? – summers are simply hotter droughts than winters. A recent global analysis offers 50-50 odds that in a few years we’ll cross the 1.5 degree C warming that signals a tipping point.

As we entered our Northern hemisphere summer — and after the IAWF’s Fire & Climate 2022 conference in California and Australia in May – I can join the many fire managers who focus not only on the fires but on the greenhouse gases propelling us into an era of fire-terrors.

While I was away from Wyoming managing fire responses in Arizona WHEN?, a severe weather event – a warm deluge pummeling a melting snow pack – flooded the north half of Yellowstone Park. A 100- or 1,000-year flood event closed Yellowstone while 100 miles south, my home park of Grand Teton simply absorbed heavy rains.

Sampling the fuels – and climate change

As a fire and all-risk manager, closing a road isn’t that unusual. But if the park-closing 1988 fires may have ended one climate era, these 2022 floods mark the new era — the hydrocene joins with pyrocene, all courtesy of our Anthropocene.

The injured infrastructure and landscape should raise welts in our humility. But beyond the road-closing floods and fires, I’ve come to observe climate change every summer day, rainy or dry.

In my work as a fire monitor and fire analyst in Grand Teton, I have sampled fuel moistures twice a month for 30 summers. We identified seven sites, representing different components of the ecosystem and its burning patterns. Among the fuels were sagebrush, lodgepole pine, mixed conifer. Season after season our team? made our small cuts, clipping and weighing the wet weight, putting the samples in the 100 C drying oven, calculating the difference from wet to dry.

Some summers the fuels cured earlier, some they barely cured at all between the rains (and snow) of June, July and August. Sometime around 2000 this began to change and by 2010 the air and the ground felt and smelled like drought. The sticky sweet terpenes of sagebrush and lodgepole were drier, losing a bit of perfume, and carried less water weight.

I came to know climate change, here in the Tetons, is as a lead fire monitor, a position no longer funded directly but somehow (thankfully) the park finds a way to fund my role each spring.

One of my duties is to collect fuel moistures and track the potential impact on each season’s fires; this research supports a long-term commitment to wildland fire use – a strange phrase to anyone who doesn’t work fire in large, fire-adapted landscapes, although it’s no stranger than prescribed natural fire, the term that framed my early seasonal career.

It’s 2022. Researchers with decades in the climate analysis world warn we have less than five years to fix our mess — though Michael Mann has observed that if we act swiftly there may be a quicker resilience and recovery than predicted.

Perhaps it’s time to simply accept that all flames in vegetation and non-built environments are climate fires. (Just as we should label any release of greenhouse gasses as climate destroying.) Some fires may help us maintain ecosystem services, fixing carbon in the roots and in carbon-balanced, fire-adapted landscapes. These are beneficial fires. Some may burn hotter than currently adapted normals — wounding the functions of ecosystems and releasing more carbon than sequestered. These are destructive fires. All are fires burning within a climate that’s changed and changing exponentially from prior burn conditions, those amazing natural fires of my middle years.

The phrase from the 1988 fires in the Tetons and Yellowstone was “Burn, baby, burn,” an exclamation of awe about fires burning on a 150- to 300-year cycle. At what may have marked the beginning of the closing of the “natural fire” era, these fires burned at a historic yet normal scale. We are now at an abnormal scale. The phrase for the 2022 fires and beyond? Perhaps “If it hasn’t burned yet, just wait.”

For me, the natural fire era began in 1984, when I first worked fire. Later jobs at Saguaro National Monument (now Park) helped me gain trust in fire as a force that humans and the landscapes could live with.

Much is similar each season, some changed. I’m greeted each spring by a marmot who lives under the seasonal cabin’s porch, a moose who prunes the cottonwood by the creek. We’ve endured and mostly absorbed beetle kill in the mixed conifer and are more concerned with the blister rust killing high elevation white bark pines.

And twice each month we sample the fuels, when we aren’t interrupted by snow or rain, limited staffing, or responding to fires. We sample live herbaceous and live woody and dead fuels at seven sites around the park, representative of sagebrush and lodgepole and mixed conifer habitats.

The analysis – fuels are more available

When we analyzed the first two decades, from 1992 to 2022, we began to observe a drying trend that began around 2000. This was most noticeable in the heavy dead and down logs, the 1,000-hour fuels that require 1,000 hours (roughly 40 days) to significantly dampen or cure. These fuels were reaching an availability to burn a week earlier and later each season, and averaged drier each season.

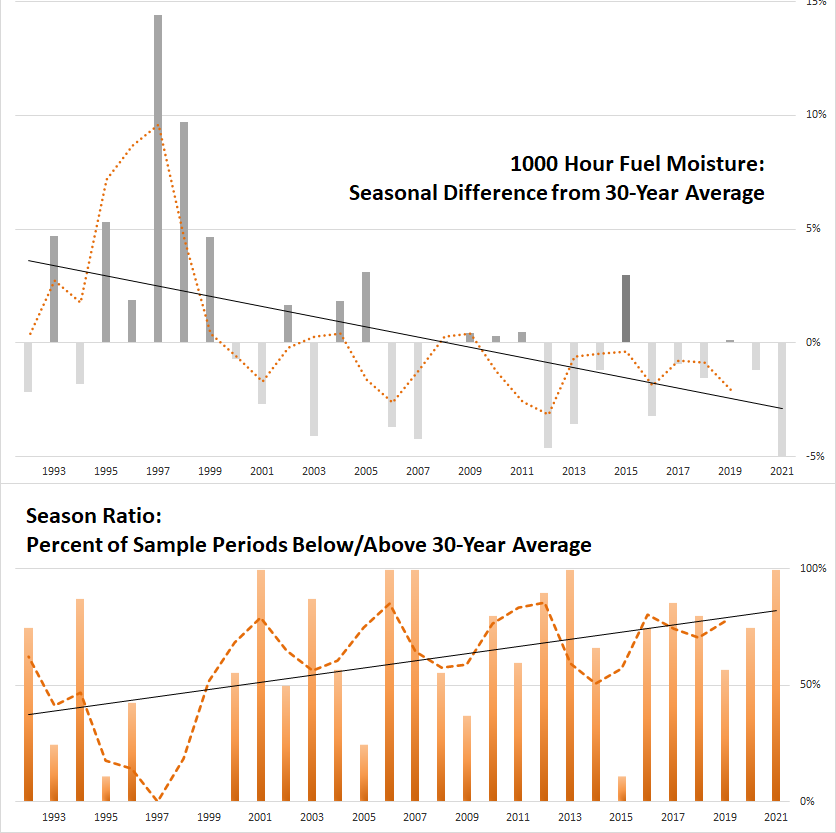

After 30 years of sampling, we asked our questions slightly differently. For all related fuel types in the sagebrush and forests, we charted whether an entire sampling season overall was wetter or drier than average. And for the 10 to 12 sample periods each season, what was the ratio of sample weeks that were drier or wetter than average for that specific period?

And what we’re observing and experiencing matches the analysis and projections of researchers, the field samples match the probabilistic-focused.

The graph of the 1,000-hour fuel moistures illustrates the trend we discovered in all fuel types and habitats. After around the year 2000, each season was trending below average. And the ratio of the number of dry sample-weeks compared to wet sample weeks was trending toward drier.

To act – informed by what we know and predict

What do we do as fire managers? What do we do as environmental leaders (and isn’t that the obligation we have as park rangers)? And as citizens?

Monica Turner and others, in a 2022 paper, support a combination of commitment and monitoring, focused specifically on this locale but with advice applicable anywhere:

“If current GHG emissions continue unabated (RCP 8.5) and aridity increases, a suite of forest changes would transform the GYE [Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem], with cascading effects on biodiversity and myriad ecosystem services. However, stabilizing GHG concentrations by mid-century (RCP 4.5) would slow the ratchet, moderating fire activity and dampening the magnitude and rate of forest change. Monitoring changes in forest structure may serve as an operational early warning indicator of impending forest decline.”

It’s good to hear the confirmation — the role of monitoring can support our management. But in many ways, our park (and National Forest) monitoring programs, from pre- and post-fire effects, and of the fuel moisture that helps determine fire return intervals and intensity, already offer an operational early warning.

Some of this monitoring occurred in the learning landscape of fire in the north half of Grand Teton. The Berry Fire of 2016 burned through two recent fires, from 1988 and 2000 (and as incident commander I issued one of two orders to close the road to Yellowstone that summer). Six years later, the research and associated monitoring support the likely scenario that forest regeneration will be diminished if the fire return intervals become drastically shorter than the habitats have adapted with. The Yellowstone and Tetons we know and cherish (some 4 million visitors each year) will remain a living and learning landscape. Yet some of the splendor we cherish will change.

We might ask — and we are asking — how might the monitoring, these early warnings, help us adapt our fire operations, next year and next decade? Or we might ask, how might the fires and floods of this symbolic yet very real landscape help us face and manage our climate crisis?

When the flames and waters cross the highways we face a physical reality: our roads are compromised by the very vehicles we seek to drive.

Who would drive into a flood or fire? Though at times I have driven through the smoke and spot fires, we don’t knowingly drive into the inferno. Yet that is what we’re doing, every day.

I continue to sample fuels. This summer, a late winter’s drying trend didn’t appear in our spring-time fuel moistures. Green-up seems normal, though some have predicted a potential flash drought later this summer, even as we deal with the aftermath of the flash floods. And I sample the fuels — clipping swigs of redolent lodgepole and sagebrush to help us prepare for our burning times, while driving the most fuel-efficient vehicle in our fleet, while asking, where are our EVs? And asking, can we please apply the lessons of the Yellowstone ecosystem, the place that has come to symbolize “nature,” in our lives and policies? This summer, not next decade, as each day our seasons are twisting toward extremes — hotter and drier, or warmer and wetter — and we still have the days to act. To re-route our lives before all the roads are closed by our floods and fires.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ron Steffens ([email protected]) has managed and studied wildfire use and climate fires on five continents. He’s a past IAWF board member, past editor of Wildfire Magazine, and teaches emergency management and communication at Prescott College in Arizona. This is a reflection written in no official capacity or intent.