With fire there’s smoke, and in the past years, smoke and smoke management has grown into a key issue for fire managers and the public. This smoke primer by a leading CDC health communicator can help clear the smoky air. The online version has links to references.

By Scott Damon

A nearing wildfire can be a terrifying situation for a number of reasons. People worry about not being able to evacuate in time. They worry about losing their homes, land, and possessions. And even if their home is not directly in the wildfire’s path, they and their loved ones can be exposed to dangerous smoke.

The Center for Disease Control (CDC), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and other government agencies are working to help educate people on how to stay safe from wildfire smoke, and have developed a number of tools for communities, medical providers, and firefighters.

Some key terms, actions to take, and information guides to consider include the following.

Particulate matter

Wildfire smoke contains a variety of air pollutants that can have an effect ranging from mere annoyance to severe health consequences. Wildfires expose people to the byproducts of burning vegetation, such as trees and grasses, and when wildfires impact communities, emissions from burning structures and furnishings, such as plastics, can release a variety of air toxics and chemicals into the air.

Short-term exposures to particulate matter (PM), also known as particle pollution, are the main public health threat from wildfire smoke. These fine particles are respiratory irritants, and exposures to high concentrations can cause persistent cough, phlegm, wheezing, and difficulty breathing. Exposures to fine particles can also affect otherwise healthy people, causing respiratory symptoms, short-term reductions in lung function, and pulmonary inflammation.

PM Health Effects

Immediate effects can include:

- Coughing and trouble breathing

- Stinging eyes

- Scratchy throat

- Runny nose

- Irritated sinuses

More serious outcomes can include:

- reduced lung function,

- bronchitis,

- exacerbation of asthma and heart disease, including heart attacks, heart failure, and abnormal heart rhythms, and

- premature death.

Short-term exposures (i.e., days to weeks) are also linked with increased premature death and aggravation of pre-existing respiratory and cardiovascular disease. The effects of exposure can be worse for people with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), other respiratory conditions, or cardiovascular disease (CVD) as well as pregnant women, children and older adults. Someone with asthma or COPD can suffer a respiratory attack that results in a trip to the ED. For someone with CVD, excessive smoke inhalation can increase the risk of heart attack.

Taking Action to Reduce Exposure

Providing information to at-risk populations may increase their willingness to take action to reduce exposure and risk. To be effective, this information must be consistent among agencies. That’s why CDC, EPA, and several other federal and state agencies have teamed up to develop and update an array of tools for clinicians, public health officials, firefighters, and the public to help protect not only the most vulnerable populations, but anyone who might be at risk of wildfire smoke exposure.

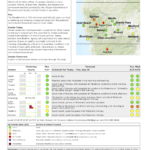

These tools all utilize the Air Quality Index (AQI). The AQI is EPA’s nationally uniform index of both real-time and forecasted air quality for specific regions. Simply put, the AQI is a yardstick that runs from 0 to 500. The higher the AQI value, the greater the level of air pollution and the greater the health concern. The AQI focuses on health effects different individuals, depending on their risk factors (e.g., asthma, COPD, age), may experience within a few hours or days after breathing polluted air. For example, an AQI value of 50 represents good air quality with little potential to affect public health, while an AQI value over 300 represents hazardous air quality. AQI values below 100 are generally thought of as satisfactory. When AQI values are above 100, air quality is considered to be unhealthy—at first for the most vulnerable groups, then for everyone as AQI values get higher. Information about the AQI, including current and forecasted air quality levels, is on the interagency AirNow website (www.airnow.gov). Information about the status of current fires is on the Fires: Current Conditions web site (https://airnow.gov/index.cfm?action=topics.smoke_wildfires). In addition, EnviroFlash, a free service offered by state or local environmental agencies in partnership with the EPA, provides daily e-mail forecasts or real-time updates based on the location and AQI level that the user selects.

Wildfire Guide and Fact Sheets

Wildfire Smoke: A Guide for Public Health Officials, more often called simply the “Wildfire Guide,” was first developed in 2001 and later revised and updated, in 2008, by the California Department of Public Health, along with other state and federal agencies. It was updated again in 2016 to reflect a much stronger fire-related evidence base through a collaborative effort of many partners, including EPA; CDC; the US Forest Service; the National Park Service; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories; the Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Units network; and the California Department of Public Health, Air Resources Board, and Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. The Guide helps local public health officials prepare for smoke events, take measures to protect the public when smoke is present, and communicate with the public about wildfire smoke and health. The Guide includes information on the composition and characteristics of wildfire smoke and the health effects of smoke exposure, including which populations are most vulnerable to those effects, specific strategies to reduce smoke exposure such as communicating about PM levels and other public health actions, and advice on unified public health response to a wildfire smoke event. In addition, the Guide features several short fact sheets for the public, covering topics including preparing for fire season, reducing exposure, protecting children, indoor air filtration, respirator use, and protecting yourself from ash.

PM Web Course for Health Professionals

Evidence has shown that the public is much more likely to take action to reduce air pollution exposure if informed about the risk from a health professional. This is why EPA and CDC developed a web course for health professionals, “Particle Pollution and Your Patients’ Health,” that offers continuing education credits for doctors, nurse and health educators. This course provides the most up-to-date information about the health effects of PM, the most important pollutant in wildfire smoke for the relatively short-term exposures (hours to weeks) often experienced by the public.

The web course provides a general overview of the mechanisms underlying the effects of particle pollution on the heart and lungs, its clinical effects, and actions that healthcare professionals can take to encourage at-risk patients to lower their exposure and risk. It further describes the biological mechanisms responsible for the cardiovascular and respiratory health effects associated with exposure to PM, and provides educational tools to help patients understand how PM exposure can affect their health. It also shows how providers can help patients learn to use the AQI to protect their health. While the course focuses on all types of PM exposures, exposure scenarios, and health effects, it is especially useful for dealing with smoke events, including a section on high PM events, such as wildfires, and steps individuals can take to reduce smoke exposure during such events.

The PM web course is designed primarily to assist healthcare professionals in protecting the health of their patients at highest risk from the adverse effects of wildfire smoke. It can also be used by state, local, or tribal organizations to help design smoke management programs, implement basic smoke management practices and develop required or voluntary mitigation and/or emergency response and contingency plans. Tools included in the course can be downloaded without taking the course and include pieces covering how smoke from fires affects health and even tips on reducing emissions from wood-burning appliances.

CDC Information

In addition to these, CDC features a wealth of information on wildfire smoke and health on its web pages. CDC provides information for members of the public at risk of wildfire smoke exposure, tips for pregnant women and parents of young infants, and other advice focusing on air quality and health.

+

About the Author: Scott Damon is the Health Communication Lead for the Asthma and Community Health Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In this role, he develops and oversees CDC’s communication on asthma and respiratory health issues, including biomass burning, air pollution, and indoor air quality issues like carbon monoxide and mold.