By Tom Harbour

Fires which occur outside buildings, improvements, and structures, whether fueled by grass, brush, forest, timber, or other materials, are the “wildland fire” we deal with in the fire service. It can take the form of thousands of acres of trees on fire, the purposeful burning we do to improve ecosystems, or the small vacant lot grass fire, but we refer to them all as wildland fire. These were the fires confronted by our ancestors, that we continue to struggle with to this day. And with more than one billion burnable wildland acres in the US, every day of the year some part of the American fire service is dealing with wildland fire.

Too many of our brothers and sisters in the fire service are dying in the line of duty while fighting fire in the wildland environment. Data suggests wildland firefighters die at a higher rate than those involved in structural fire response, and the emotional, social and fiscal costs of wildland firefighter death, accident, and injury weighs heavily on each of us. These costs have generation-long impacts that are too devastating to simply absorb as “the price of doing business.” Unless we choose to change the ways in which we operate, too many wildland firefighters will continue to die in preventable incidents. We need change – positive change. We need to improve our strategies, tactics, and human factors training in wildland fire so more of us live long and healthy lives after engaging.

The National Fallen Firefighters Foundation (NFFF) has taken on the task of working to coalesce the many voices of wildland fire in support of reducing line-of-duty death (LODD), accident, and injury among our firefighters. As an initial step, the NFFF conducted a wide-scale needs assessment of all populations involved in wildland fire response, including natural resource management organizations. After a year of focused inquiry, the NFFF presented their findings and engaged a representative sample of American wildland fire leaders in active discussion at a meeting held outside Washington D.C., on April 17, 2018, ahead of the Congressional Fire Service Institute’s annual National Fire and Emergency Services Dinner & Symposium.

This group of leaders was asked for their input, review, comment, and commitment to a series of actions and recommendations emanating from the NFFF’s needs assessment. The event began with thoughtful opening comments by leaders from the NFFF, US Fire Administration, Wildland Firefighter Foundation, Congressional Fire Service Institute, US Department of Agriculture (home of the Forest Service), and US Department of the Interior (home to four federal wildland fire organizations). Attendees represented a broad range of additional stakeholder organizations, including:

- National Volunteer Fire Council

- International Association of Fire Chiefs

- International Association of Fire Fighters

- International Association of Wildland Fire

- International Fire Service Training Association

- National Fire Protection Association

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health/Center for Disease Control

- National Institute of Standards and Technology

- National Wildfire Suppression Association

- State forestry organizations

The diverse group of leaders assembled thoughtfully considered actions in both the large group and smaller, more focused, discussion sessions. It was important for attendees to understand why the NFFF, at this juncture, was prepared to engage in this effort to support the wildland community. The NFFF’s intention to form and sustain collaborative relationships and build coalitions among organizations with the support of each organization’s leaders will be important tools in advancing national efforts to reduce wildland fire LODDs. Widely acknowledged for reducing LODDs among structural firefighters through programs under the Everyone Goes Home® umbrella, the NFFF now proposes to leverage their strengths and resources to do the same for wildland firefighters. Their assets and expertise include:

- More than a decade of experience focusing on firefighter health and safety.

- A broad array of tools, programs, and resources that can be easily adapted for use by the wildland fire community.

- A proven track record of working with diverse agencies to unite efforts in pursuit of the common goal of reducing firefighter fatalities. NFFF is known for its efforts in recognizing each agency’s unique organization and culture, then tapping into those characteristics to build a cohort that strengthens partnerships and collaboration – keys to successful change.

At the April meeting, leaders heard the results of the NFFF’s comprehensive survey of stakeholders, as well as a detailed report of six “listening sessions.” These sessions were a series of focus groups held across the country to solicit direct feedback from firefighters representing the range of departments and organizations who deal with wildland fire. One of the resounding themes heard during these sessions was the need to work to end the perceived “worlds apart” between wildland and structural firefighters and organizations. Firefighters acknowledged the need to work and train collaboratively across organizations, and clearly want to build bridges and bring both worlds together. It is evident that from leadership down, there is consensus that we need to bridge the thinking which separates natural resource organization firefighters from those in the structural fire service. The frequency of the two groups coming together to mitigate incidents makes a stronger collaboration critical to reducing the LODD and injury incidents.

Community risk reduction was also a common topic of discussion at the listening sessions. Participants acknowledged the need to engineer a future where wildlands are less flammable, and communities are better equipped to deal with wildfire. However, participants also recognize that the ”Design it Out” option for wildland fire is a strategic vision of a grand scale that will take an extensive investment of time, people, and funding. Those investments suggest far-reaching resolutions in the wildland fire environment that will not likely transpire in the immediate future. While the participating firefighters want leaders to continue to advance advocacy for these efforts at the state, local and federal levels, they recognize that they can’t wait for that future to become reality, and other, more immediate, actions are needed to improve their safety.

Participants stressed the need for accountability at all levels, and the willingness to “do more” at the individual, crew, and company level to increase personnel safety. Firefighters clearly want to reduce LODDs and recognize that reducing fatalities is intertwined with other issues. These include the lack of access to good data, the need for firefighter physicals and fitness testing to develop a baseline for health and wellness, and a growing awareness of the gaps in available resources supporting the emotional wellness of personnel and their families.

Another dominant topic at the listening sessions was risk management. While risk management is a well-known concept in the structural fire service, natural resource management agencies with wildland fire responsibility are just now using the term more frequently. It is evident, though, that the specifics of the application of risk management are neither understood nor utilized across organizations.

All of us involved in wildland fire know that risk is inherent to our profession. Firefighters, fire managers, fire leaders, fire chiefs, etc. all purposefully engage a hazard – whether that hazard is fire we light (prescribed fire) or unplanned fire (wildfire). Currently, our willingness to accept risk in response to wildfire is out of alignment with the biophysical reality we face. We still respond to fire in the same manner we always have, without adjusting to the reality of today’s fires.

We routinely accept risk, but we never accept loss. But doesn’t accepting risk mean we are accepting the chance of suffering loss? There is a clear and evident need to have the difficult conversations surrounding risk. This will include frank discussions about what the community is willing to risk, and what the community is willing to lose when fighting a wildland fire. That discussion, and multiple other factors, continue to cloud the application of risk management within wildland fire response, and that ambiguity leads to the conflict, including:

- There is no commonly accepted definition of risk management nor application of risk management principles among the wildland community, including those final decision-makers (agency administrators).

- Expectations regarding the acceptance of risk are different in protecting public vs. private lands.

- Managing fire through prescribed fire reduces risk but is often not an option. Laws, rules, regulations, practice, and other influences often limit wildland fire management.

- Managing community building practices reduces risk but is often difficult to achieve.

- Individual tolerances for risk vary widely and are influenced by many factors.

- Perceptions of risk levels and risk tolerances can vary between levels of leadership on the fireground and between leaders and firefighters.

- The public seems conflicted about risk, so firefighters are conflicted about risk.

- Having one partner, or group of partners perceived as being “risk-averse” can lead to additional risk burdens for other firefighters, landscapes, and for communities.

The discussion surrounding risk management will be critical to undertake and will impact wildland fire policies and tactics for decades to come. The sooner this dialogue can start, the sooner the wildland community can begin to establish a common vision. All stakeholders (firefighting personnel, leaders [agency and political], public, and researchers) need to be present at the table to discuss values at risk (monetary, biological, egos, ownership, etc.). One of the root questions to ask is, “What are we protecting or not protecting, and what are the positive and negative effects of these decisions in the long- and short-term?” We should be clearly asking upfront if the gains are worth the exposures – the discussion about values and trade-offs is critical.

The wildland fire service leadership present at the April 2018 meeting was able to reach consensus on initial steps to take to improve the health and safety of wildland firefighters. Below is a series of recommendations for the agencies present, guided by the experience and oversight of the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation, to begin to be implemented immediately to reduce injuries, deaths, and accidents among wildland firefighters.

STRATEGIC AND TACTICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

- “Two worlds apart” must become closer. Natural resource management and fire service organizations need to become worlds who learn to support one another in wildland work.

- Increase application and understanding of risk management concepts.

- Change the wildland fire paradigm from, “Can we accomplish the mission?” to “Can we survive the mission?” As an industry, we need to ask, “How can we respond in a manner which protects citizens, sustains landscapes, and allows reasonable risk for responders?”

- Change the expectation that we can be successful in EVERY wildland mission ALL the time.

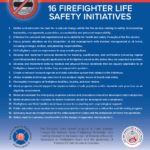

- Increase awareness of the 16 Firefighter Life Safety Initiatives (16 FLSIs) among wildland firefighters. (see graphic below and more info at https://www.everyonegoeshome.com/16-initiatives/). The 16 FLSIs are strategies for implementation of the EGH program but are not well known among wildland firefighters. To broaden awareness and utilization, we can: a). Explore whether the 16 FLSIs can be tweaked to become more broadly inclusive of wildland culture; b) Better explain the interaction between the wildland community’s well known “10/18/LCES/Watch Outs” with the 16 FLSIs; and c) Develop materials to explain implementation of the 16 FLSIs within a wildland context.

- Adapt effective Everyone Goes Home® tools for wildland use and target marketing of these tools to wildland fire agencies/organizations. Existing and future EGH tools can be made more inclusive of wildland firefighters and organizations. Targeted marketing efforts, beginning at the state wildland fire academy level, will broaden exposure of wildland firefighters EGH.

- Utilize state EGH Advocates to provide outreach to wildland fire organizations.The NFFF’s well-developed network of state-based volunteers can be used to advocate for the EGH program and provide training to wildland fire organizations. Special effort also needs to be made to recruit additional Advocates from within the wildland fire community.

- Increase the use of medical screenings and fitness/wellness programs to improve the health and safety of all firefighting personnel. Identification of pre-existing risk factors through NFPA 1582 medical screenings and increased adoption of holistic health programming such as IAFC/IAFF’s Fire Service Joint Labor Management Wellness Fitness Initiative should be prioritized.

- Enhance the ability of the wildland fire service to take care of its people prior to and in the aftermath of a firefighter injury or fatality. Firefighters want access to tools to support emotional wellness for themselves and their families, such as those that were developed to fulfill the NFFF’s FLSI 13.

- Continue to focus research and prevention efforts on the major categories of line-of-duty death and/or injury in wildland fire accidents. These include: a) Medical incidents, which include cardiac events, rhabdomyolosis, hyperthermia, occupational cancers, etc.; b) Motor vehicle accidents, including unsafe driving, lack of seat belt use, etc.; c) Burnovers/entrapments; d) Aviation accidents; and e) Snags/rocks/rolling debris.

- Introduce results of research products and findings at all levels of the organization, down to the lowest level applicable. There is a tremendous amount of good science information which is not being effectively utilized. This information should be used to inform and improve practices, training, and education.

- Data problems need to be reconciled. While the NFPA has done much work in this area, currently there is no authoritative national census on wildland firefighters across the spectrum of agencies and organizations.

- Increase marketing efforts for the National Wildland Fire Cohesive Strategy. There is little overall awareness for the National Wildland Fire Cohesive Strategy. Where it has been implemented, it has demonstrated effectiveness. These “points of light” (including Central Oregon, Flagstaff, GOAL), where the “worlds apart” are now working together, can be used to model implementation.

The session closed with an inspirational call to action from the State Forester of Florida, chair of the National Association of State Foresters Wildland Fire Committee. He stated that clearly, there is significant work to do to change. Nevertheless, change we must. Every year, wildland fires engage thousands of firefighters from federal, state, local, and private entities. While they understand the need to “take action at the lowest level” to improve their own health and safety, the NFFF’s listening sessions revealed that these firefighters also have high expectations for leaders. They are counting on us. This revelation demands that the wildland community embark on a more vigorous campaign to reduce LODDs, which is a worthy goal for all and a common starting point for better collaboration. We need to enlist everyone’s help, and have every agency with an interest in the wildland fire problem engaged. Fortunately, we can rely on the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation to lead the way.

+

Download a printable tri-fold brochure focused on wildland firefighters: https://bit.ly/2PI36HZ

+

Tom Harbour, a board member of the IAWF since 2018, is a recognized expert in wildland fire and aviation management policy and operations and served as National Director of Fire and Aviation Management (National Fire Chief) for the US Forest Service.