PHOTO BY GAVRIIL XANTHOPOULOS

SUPPRESSION VERSUS PREVENTION

THE DISASTROUS FOREST FIRE SEASON OF 2021 IN GREECE

BY GAVRIIL XANTHOPOULOS, MILTIADIS ATHANASIOU, AND KONSTANTINOS KAOUKIS

The forest fire season of 2021 in Greece was exceptional; the volume of hectares burned, and the fire-caused damages, led to heated debate in parliament and the media about the country’s fire-management organization.

The season was characterized by an early start of significant fires that continued throughout the summer, with increasing firefighting problems as time progressed, resulting in serious devastation.

In the aftermath, besieged by intense criticism from media, opposition parties, and residents of fire-affected communities, the government promised changes and the elimination of such disasters.

In the subsequent months, there was a lot of talk and even some action toward change; unfortunately, yet again, the focus is on more firefighting capacity rather than holistic forest fire management.

TIMELINE

The official forest fire season in Greece extends from May 1 to Oct. 30. A fire on the island of Andros in the Aegean Sea on April 4, 2001, burned about 500 hectares of low shrubs and agricultural cultivations under strong winds and was stopped the next morning with the help of rain.

This fire made the news because it was early in the year, and because the General Secretariat of Civil Protection and the fire service demonstrated the policy they were to follow for the rest of the year – evacuating many villages in the vicinity of the fire.

The purpose of the policy was to avoid fatalities at any expense. The emphasis on evacuation was the result of heated political clashes in the aftermath of the East Attica fire of July 23, 2018, in the settlements of Neos Voutzas and Mati, which had caused 102 fatalities.

Following that disaster, the opposition had accused the government of failing to evacuate people in an orderly and timely manner. In 2019, the main opposition became the new government, and avoidance of firefighter and civilian fatalities became a central objective.

Contracted aerial resources, especially in the fire season of 2021, were strengthened impressively, to try to reduce the chance of devastating fires, while ordering evacuations during early stages of a potentially serious fire became the norm.

On May 19, 2001, at a time of the year when grasses are still largely green, a fire started under very strong wind near the Schinos settlement in Corinthia, 60 kilometres west of Athens. The vegetation was mainly pine forest. First responders focused on evacuation of people and the protection of homes. The fire spread through the night and, given the delayed response on the ground and limited aerial support next morning, became large, burning both forest and agricultural cultivations.

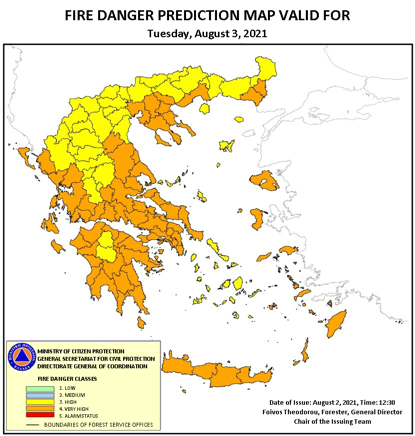

Source: General Secretariat for Civil Protection; translation Gavriil Xanthopoulos.

The emphasis, once more, was on citizen evacuation, using among other tools, alert/evacuation messages to mobile phones transmitted through the 112 Civil Protection emergency number.

After four days, the burned area reached 6,964 hectares. There was considerable debate in the media about the reasons, with some local authorities calling for more aerial resources to be available year-round.

Currently, only a small portion of national aerial firefighting resources are available outside of the fire season; the bulk of the contracted resources arrive in June and operate until the end of September. The use of 112 for early warning over a broad area, the emphasis on early evacuation of villages (even when they were not threatened by the fire), aiming to eliminate the risk of fatalities, and a defensive stance by firefighters for the same reason, became apparent as policy cornerstones for the rest of the fire season.

As the fire season advanced, the pattern described above was repeated over and over. However, as the larger-than-ever aerial fleet of national and contracted resources built up by the middle of June, massive initial attacks from the air managed to offset any weaknesses on the ground. The contracted aerial resources included 10 contracted S-64 AirCrane helicopters. By the end of July, however, as the fire danger grew with a heatwave that brought increasing temperature and dropping relative humidity, the first signs that the situation could not be kept under control became evident. Two significant fires in Achaia that resulted in serious damages, and a large fire on Rhodes Island, presented serious challenges to the firefighting system.

The heatwave, with temperatures exceeding 40 C in most of the country and reaching 47 C in some locations, started July 28 and had an unprecedented duration of 10 days, according to the National Observatory of Athens. This was reflected in the fire danger prediction map for the country that is issued daily by the General Secretariat for Civil Projection (Figure 1).

PHOTO BY GAVRIIL XANTHOPOULOS

On Aug. 3, around 13:20, a fire started 18 kilometres north of the center of Athens, near a settlement called Varympompi, which is one of the wildland-urban interface (WUI) areas that exist around the city. At the time, temperature had reached 42 C and relative humidity had dropped close to 10 per cent while the wind blew at about 8 km/h an hour with gusts exceeding 15 km/h. The fire grew, mainly through radiation and profuse short-distance spotting as the wind was not strong.

The ground resources focused on saving property, leaving fire control to the aerial resources. However, at such low relative humidity, the fire kept restarting after the aerial drops. Since aerial fire fighting was not followed by effective work on the ground by hand crews and dozers, and the suppression efforts consisted of sporadic and sparse attempts, there was no gradual (stepwise) containment of the wildfires, and the overall fire fighting was ineffective. Varympompi and all other neighboring settlements were evacuated with a concerted effort by police. About 80 buildings, mainly homes but also some businesses, were destroyed.

With a fleet of helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft waterbombers fighting the fire, it was put under control by the middle of next day, with estimates of burned area ranging between 1,300 and 3,000 hectares. However, this fire fight came at a heavy cost. Another fire that had started near the town of Limni, located by the east coast of the forest-rich north part of Evia Island, 95 kilometres north of Athens, did not receive the necessary attention and aerial support. This was confirmed by various sources including the elected head of the prefecture of Evia and the two local mayors. Exhibiting very high fire intensity and after threatening Limni, the fire started growing inland. Simultaneously, four other aggressive fires had started in Peloponnese, the most threatening being the one in the prefecture of Ilia, which expanded in the direction of the archaeological site of Ancient Olympia. At that point, on Aug. 4, there were serious doubts about the capacity of the Greek firefighting mechanism to handle the situation, and the government requested the support of the European Union Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM). Over the next three to four days, other non-EU countries mobilized and sent resources and firefighters as well.

On Aug. 5, in the middle of the day, the situation became much worse, when the Varympompi fire, which had been controlled and was passively guarded, restarted. This fire soon crossed the eight-lanes wide Athens-to-Thessaloniki National Road at three different points. In the next two days the fire burned through more settlements, destroyed the Tatoi estate where the summer palace of the ex-king is located, and was finally stopped after reaching the core of the Parnis National Park to the west and the shores of Marathon Lake to the east. The final burned area was 8,377 hectares. Two volunteers died fighting the fire and a third succumbed to his burns six months later.

Figure 2: An image acquired by one of the Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellites on Aug.8, 2021, shows the wildfire of northern Evia with a towering convection column

(Source: https://www.copernicus.eu/en/media/image-day-gallery/evia-wildfire-greece)

In the next days, without fierce winds but with intense fire behavior due to heat and dryness, the other fires kept growing. In northern Evia, the fire, spreading in many cases against the wind, developed towering convection columns (Figures 2) finally stopping at the sea. At 50,000 hecatares, the Evia fire became the largest fire in modern Greek history, in a year during which the country had the strongest firefighting capacity. According to fire service statements, the co-ordination center had to manage up to 102 aerial resources. Simultaneously, the fires in Peloponnese also became very large: the fire in Ilia-Gortynia reached 15,000 hectares; the fire in Messinia 5,100 hectares; and the fire in Lakonia (Mani) 10,100 hectares, devastating both forest and agricultural lands.

By Aug. 11 the situation started being brought under control. However, as discussions about what went wrong were hot in the media and the political arena, two more destructive fires in Attica, on Aug. 16, burned about 9,800 hectares.

The final burned area in 2021 exceeded 130,000 hectares, in addition to extensive damages to houses and infrastructure, despite unprecedented international help that came to aid Greece with fire fighting in August, comprising both aerial resources and ground firefighters. Aid included help from Austria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, and Sweden, which was provided in the frame of the European Union Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM), as well as bilaterally provided (or offered) help from Egypt, Israel, Kuwait, Moldova, Qatar, Serbia, Switzerland, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.

BY GAVRIIL XANTHOPOULOS

DISCUSSION

The memory of the 2018 disaster in Eastern Attica, with 102 fatalities, played a major role regarding the selected, quite naïve, fire-management approach. As those deaths had become a central issue in the political arena, the government wanted to avoid fire fatalities at any cost. This was stressed on multiple occasions. Thus, rather than maximizing initial attack efforts from both air and ground, the selected approach was to mainly use aerial resources for this task, with firefighters mostly working on the protection of homes, often remaining on roads and avoiding entering the forest until the flames were subdued by the aerial water drops.

This policy was supported by a steep increase in the contracted aerial resources: added to the national resources, the total reached 71 planes and helicopters, before the arrival of international aid. Simultaneously, and in addition to the messages for evacuation from the 112 emergency number (76 messages, of which 66 were for evacuation), strong police forces were deployed to actively push people to evacuate.

Whereas in some cases fire behavior, topography, accessibility and building characteristics justified the order for evacuation, in most cases such criteria were not considered. Thus, pushing indiscriminately for evacuation, the firefighters had to try to defend the abandoned homes rather than trying to control the fire perimeter.

In a difficult fire season, such as 2021, this approach failed, as the aerial resources were not able to achieve fire control without serious support on the ground.

The excessive use of 112 for warning and evacuation messages – especially in cases when it is not really needed, or with directions that are rather vague (which was the case on some occasions) – may result in loss of importance and effectiveness; Aesop’s fable about the boy who cried wolf should always be kept in mind.

As for what could be done differently, it is necessary to point out the need to strengthen fire prevention, regarding education and preparation of the population and proper management of the landscape. With a barely functional Forest Service due to aging personnel, reduced funding and poor morale, forest management is quite poor and fuel accumulation high, and this needs to be corrected; this had been pointed out two years earlier, in a report by an independent commission, chaired by Prof. Johann Goldammer, who was appointed by the government after the 2018 fire disaster in Eastern Attica, and was tasked “to Analyze the Underlying Causes and Explore the Perspectives for the Future Management of Landscape Fires.”

PHOTOS BY MILTIADIS ATHANASIOU

The over-reliance on aerial resources and the unorthodox approach to ground fire fighting must change. This has been pointed out numerous times, not only in the report of the independent commission, but also by many researchers and writers, mainly from the domain of forestry but also and even the former minister of Agricultural Development and Food.

Effective initial attack and efficient management of large fires should become absolute priorities. Limiting the cost of aerial resources and improving their contribution through better co-ordination with ground forces will not only improve effectiveness but also efficiency. Thus, there could be more funding available for prevention.

High quality pre-suppression planning, especially in wildland-urban interface areas, is necessary to improve efficiency and safety; it should include identification of locations where populations may be at high risk in case of fire, and specification of criteria and priorities for evacuation. The local authorities and the population should be informed and prepared accordingly, in advance of the fire season.

Furthermore, some other important changes should be introduced, following fire management examples elsewhere, namely:

- Formal introduction of the use of fire in fire suppression – a time-honored technique, necessary in indirect attack, which has been forgotten in Greece in the last few decades. As of March 2022, the government introduced a law recognizing that fire can be used as a firefighting tool when considered necessary by the fire service, leaving drafting of the technical aspects of how to use it as a next step.

- Creation of a legal framework for the use of prescribed burning for fuel reduction and for other forest land management objectives.

- Recognition that all forest fires are not bad, thus ceasing to use burned area reduction as the only criterion for fire management success. Even under the extreme conditions of 2021, within some portions of the burned areas, fire severity was relatively low either due to the presence of less flammable species (Figure 3) or because of the resilient agroforestry landscape.

(Image source: NASA WorldView, annotation: Gavriil Xanthopoulos).

A host of other issues and changes can be identified and discussed. Actually, the government has already tried to introduce improvements, mainly in the direction of fire suppression, such as hiring 500 young firefighters to create helicrews and contracting even more aerial resources; it has also indicated its willingness to support fire prevention. However, in many cases, a lot has to do with how changes are conceived, designed, and applied. Serious input from modern forest fire science is needed. Without well-planned changes, if Greece continues only to pile up resources, the problems will become evident again in the first difficult fire season. With current weather trends under climate change, it is more than likely that this will happen quite soon.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gavriil Xanthopoulos is an associate researcher specializing in forest fires at the Institute of Mediterranean Forest Ecosystems of the Hellenic Agricultural Organization “Demeter”. He holds a B.Sc. in forestry from the Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, Greece and M.Sc. and PhD degrees in forestry with specialization in forest fires from the University of Montana. He has been active in European forest fire research for more than 25 years, with a parallel involvement in many aspects of operational fire management, post-graduate teaching and forest fire management training. He is a member of the board of directors of the IAWF and as an associate editor for the International Journal of Wildland Fire. His research interests include forest fire policy, fire prevention, fire danger rating, fire behavior, fuel management, firefighting, post-fire rehabilitation, forest fires and climate change, and new technologies in fire management.