SHARING CIRCLES: CIRCUMPOLAR INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVES ON WILDLAND FIRE

BY ANNA DEGTEVA AND CAMILLE VOURC’H

Sharing Circles are essential elements of Indigenous Peoples’ cultures and decision making. In the Circle, everyone is equal and invited to share information and worldview, facilitating a sense of unity, good communication, learning, and finding consensus. Sharing Circles are therefore necessary in Arctic Indigenous societies for making and implementing decisions.

The Arctic Council is the leading intergovernmental forum that promotes cooperation and coordination among the Arctic States and Indigenous Peoples on issues of common concern, particularly environmental protection and sustainable development. The unique feature of the Arctic Council is that in its political and expert-level work, it equally welcomes all perspectives and knowledge available, including scientific and Indigenous Knowledge from the circumpolar Arctic.

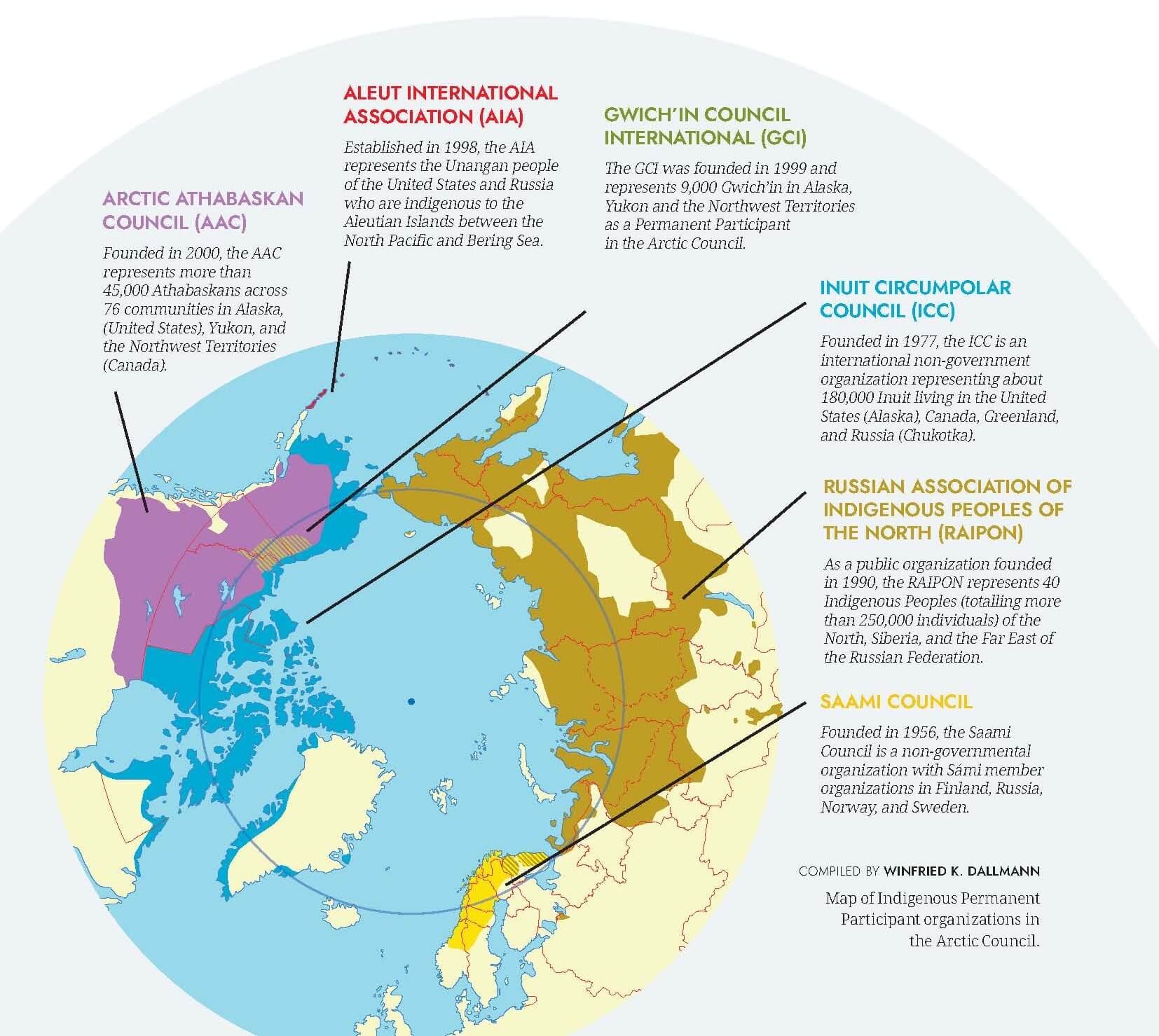

More than 500,000 Indigenous Peoples live in the Arctic, spanning three continents, 30 million square kilometers, and seven of the eight Arctic States. The Permanent Participant organizations represent Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic Council.

The Arctic, home to Indigenous Peoples who have stewarded its lands since time immemorial, is facing escalating wildland fires.

Thanks to the persistent advocacy of the Gwich’in Council International and Norway’s support, wildland fires emerged as a priority issue in the Arctic Council, leading to the launch of the Wildland Fires Initiative during Norway’s Chairmanship (2023 to 2025).

All six Indigenous Permanent Participant organizations of the Arctic Council actively engaged in the Wildland Fires Initiative: the Aleut International Association (AIA), Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC), Gwich’in Council International (GCI), Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON), and Saami Council.

To address the rising frequency and intensity of Arctic wildfires, the Permanent Participant organizations led a series of Sharing Circles (see sidebar). These events gathered Indigenous representatives from across the Arctic, alongside researchers, Arctic State officials, observers, and other stakeholders beyond the Arctic Council.

Sharing Circle on Wildland Fire online – November 2021

Wildland Fires Sharing Circle: Arctic Indigenous Peoples on Fire Practices, Changes, and Impacts – February 2024

Living with the Fire: The Overlooked Community Stories from Arctic Wildland Fires Arctic Circle Assembly – October 2024

Sharing Circle on the Role of Indigenous Fire Management in Climate Mitigation and Adaptation Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – COP29 – November 2024

Indigenous Sharing Circle on Arctic Emergency Management Conference -March 2025

Sharing Circle: Arctic Indigenous Peoples on Fire Practices, Changes, and Impacts took place in Tromsø, Norway, in February 2024 and became one of the decisive contributions of the Wildland Fires Initiative. Building on earlier collaborations, including the 2021 online sharing circle, the discussion during the Tromsø event powerfully affirmed the value of circumpolar Indigenous perspectives on fire.

ARCTIC WILDFIRES AS GLOBAL ISSUES

EDWARD ALEXANDER, GCI

Edward Alexander, co-chair of Gwich’in Council International and co-lead of the Wildland Fires Initiative, set the scene by emphasizing that boreal wildland fires in the Arctic are not just a local crisis, but threaten the entire planet. Since 1965, Alexander reminded participants, more than 65 per cent of his homeland has burned due to increasingly severe wildland fires, and he warned that boreal burnings in Alaska, Yukon, and Siberia expose yedoma (ancient and ice-rich permafrost), which holds hundreds of gigatons of greenhouse gases, enough to drastically alter life on Earth.

Fire is essential to the Gwich’in Nation for heat and gathering, culture and language, ways of life, and renewal of the landscape, Alexander shared. For millennia, the Gwich’in practiced cultural spring burns in meadows and grasslands, timing them just before the ground defrosts so the roots and seeds are not damaged. These cultural burns promoted biodiversity, created healthier habitats, and crucially, prevented larger, uncontrolled fires later in the season.

Edward Alexander was critical of fire suppression policies over the past 70 years that have led to dangerous fuel buildup. Instead of preventing fires, these suppression policies have made the fires more explosive, he explained. The solution, Alexander said, is to revive Indigenous cultural burning, treating fire as a tool for prevention and stewardship rather than just an emergency to suppress.

“Wildland fires in the Arctic should matter to everybody, this isn’t just an Arctic problem!” – Edward Alexander, Gwich’in Council International

FIRE AS SURVIVAL AND CULTURE

PATRICIA LEKANOFF-GREGORY, AIA

Okalena Patricia Lekanoff-Gregory, vice president of Aleut International Association, highlighted fire’s profound significance for the Unangan (Aleut) People. In the treeless Aleutian Islands, fire was essential for survival, providing warmth through stone lamps, aiding hunters in kayaks, and enabling food preparation and traditional healing practices.

Though the Aleutian Islands lack forests and wildfires, Lekanoff-Gregory noted that distant fire smoke still impacts communities. Volcanoes, another form of fire, have shaped the history of Unangan People, both destroying and renewing the land.

Lekanoff-Gregory underscored that fire is harmful but still essential, both a danger and a vital part of Aleut life, and that non-Indigenous societies could learn from better understanding this duality.

FIRE IN CULTURE AND REINDEER HERDING

GUNN-BRITT RETTER, SAAMI COUNCIL

For the Sámi, fire is both a spiritual and practical force. Gunn-Britt Retter, Saami Council’s Head of Delegation to the Arctic Council, pointed out fire’s dual nature by sharing the Sámi saying, “Fire is both a helpful friend and a strong master!,” echoing Lekanoff-Gregory’s statement that fire can be both damaging and regenerating. Retter described how fireplaces serve as communal spaces for sharing coffee, storytelling, and decision making.

Retter noted that controlled burns were used strategically in reindeer herding in the Sámi area (Sápmi) in northern Europe, particularly to create smoke to control the herds’ behaviour and protect reindeer during mosquito season. Retter also clarified that while large-scale burning to improve grazing lands for reindeer was uncommon, historical records suggest some herders used controlled burns to enhance biodiversity, as evidenced by Sámi place names, such as Buollenoaivi, which indicate past wildland fires and subsequent nutrient-rich regrowth.

Gunn-Britt Retter emphasized that understanding fire’s ecological impacts is essential for sustainable forest management and highlighted the need to integrate Indigenous Knowledge into modern environmental strategies. Retter raised a critical question for researchers and climate policy: Do controlled cultural burns emit less carbon dioxide than catastrophic wildfires?

VULNERABILITY OF INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES

VLADIMIR KLIMOV, RAIPON

Vladimir Klimov, vice president of the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North, began his testimony by sharing about the Mansi People in Siberia and their dual-natured fire goddess who nurtures when respected but ravages when ignored.

According to Klimov, this metaphor reflects Siberia’s fire crisis with record-breaking burns in 2021 and 2023. Klimov highlighted the dangerous disconnection between traditional fire practices and modern policies. While Indigenous communities like the Mansi carefully managed fire risks – collecting only dead wood and conducting controlled spring burns – outsiders now disregard these safeguards.

Tourists and settlers often spark blazes through carelessness, while laws banning traditional burning allow flammable undergrowth to accumulate. In Klimov’s homeland, rising temperatures (30 C in May), careless tourists, and abandoned land management of meadows have led to more frequent and intense wildland fires, while geographic isolation leaves Indigenous territories without timely emergency response.

Vladimir Klimov also mentioned intensified threats facing his region: underground peat fires (zombie fires) that smoulder for months, destroying plant roots and seeds, and species displacement. Changing conditions have driven black bears into Mansi lands, Klimov said, disrupting ecosystems. Unlike the brown bears – a sacred animal for Mansi – black bears are aggressive toward humans and push brown bears northward, where they attack reindeer herds of Nenets People – a dual crisis undermining both ecosystems and traditional livelihoods.

Klimov advocated restoring traditional fire practices such as controlled spring burns, and teaching youth fire stewardship as Elders once did. Klimov described community-led patrols monitoring high-risk areas as a necessary method to combat the wildland fires in critical periods and called for policy changes to legitimize traditional burning methods that successfully managed fire risks for generations.

COLONIZATION FUELS WILDFIRES

CHIEF GARY HARRISON, AAC

Chief Gary Harrison, Alaska’s Chair of Arctic Athabaskan Council, shared how traditional burning practices – summer grassland fires and winter dead spruce burns – once safeguarded forests, waterways, and food sources. In Chief Harrison’s Alaskan community, these controlled burns reduced forest fuels, prevented catastrophic wildfires, and managed spruce bark beetles. Harrison warned that without such practices, modern wildland fires burn deeper, sterilizing soils and washing ash into streams, harming salmon and trout. In addition, deforested riverbanks also raise water temperatures, further stressing cold-water salmon already impacted by climate change.

Chief Harrison highlighted that colonization and criminalization of Indigenous burning practices have disrupted traditional Athabaskan land management practices, particularly controlled burning, leading to increased wildland fire risks and environmental degradation.

Additionally, boarding schools suppressed Indigenous Knowledge and language. “Today, even our own people sometimes don’t understand why we burned,” Chief Harrison said, noting that the community is now in the revitalization process thanks to the knowledge of few Elders held from the boarding schools.

“And together as we gather around this fire that we share in common, we can come up with the solutions that we need.” – Edward Alexander, Gwich’in Council International

Chief Gary Harrison also stressed the need for better community planning, particularly in evacuation procedures. Reflecting on the Yellowknife area evacuations in August 2023, Chief Harrison criticized the failure to coordinate with Indigenous governments, noting how Elders were “shipped off alone to other communities” and young people were separated from their families and support systems.

Chief Harrison called for revitalization and legal recognition of Indigenous fire practices, and genuine collaboration between Indigenous Knowledge holders and scientists. Chief Harrison urges scientists to “push governments to legalize our practices” rather than just study them. “Our knowledge isn’t data,” he said, “It’s the solution.”

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE MOBILIZATION

HERB NAKIMAYAK, ICC

Most Inuit communities are above the treeline, but with climate change accelerating growth and shrubification, tundra fires occur at an unprecedented rate – a problem that requires the equitable and ethical engagement of Inuit People and their knowledge. To promote coexistence and recognition of multiple knowledge systems, the Inuit Circumpolar Council convened an Indigenous Knowledge Mobilization session led by Herb Nakimayak, Vice President of ICC Canada, at the Arctic Emergency Conference 2025 in Bodø, Norway. Nakimayak has joined the call of other Permanent Participants to establish a mechanism to address wildland fires issues across different levels and Working Groups of the Arctic Council.

SOLUTIONS: POLICY CHANGE AND INCLUSIVE FIRE MANAGEMENT

Indigenous perspectives on wildland fires gathered though the sharing circles show that wildland fires in the Arctic are not just a regional problem, but a global burning issue. Indigenous perspectives highlight that fire has a deep dual nature, both a danger and a necessity.

While modern wildland fires endanger food security, livelihoods, and cultures, Indigenous Knowledge and perspectives offer useful tools for collaboration on wildland fire management, knowledge sharing, and education of younger generations.

From Indigenous viewpoints, it is the responsibility of Indigenous Peoples to maintain ecological balance for all beings – not just humans – through intentional land stewardship practices such as cultural burning.

Arctic Council Permanent Participants pointed out during the sharing circles that wildland fires modify the relationship between humans and animals in unpredictable ways: as landscapes are radically altered, biodiversity is impacted and invasive species spread. Indigenous participants expressed the difficulty of overcoming 70 years of fire suppression, alongside the dramatic changes in the landscape and climate.

The Sharing Circles emphasized how deeply interconnected Indigenous Knowledge and fire management practices are, stressing the necessity to fully include Indigenous perspectives in national and global management and policy approaches. Collaboration among researchers, practitioners, governments and Indigenous Peoples will be key to inclusive and efficient wildland fire management.

The solution lies not in suppression but rather in stewardship and revival of ancient practices to prevent future disasters. In this respect, Sharing Circles serve as a powerful tool for empowering Indigenous governance and amplifying Indigenous perspectives in the policy making of the Arctic Council and beyond.