IMPROVING THE HEALTH AND SAFETY OF WILDLAND FIREFIGHTERS

A WORKSITE PROGRAM READY FOR DEPLOYMENT

BY DIANE ELLIOT, SUSANNA EK, AND KERRY KUEHL

For almost 20 years our research team at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland has been at the forefront of designing, assessing, and disseminating safety and health programs for different occupations, including career structural firefighters and other first responders.

We were founding members of the Oregon Healthy Workforce Center (OHWC), one of the original five U.S. sites funded by the National Institutes of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as Centers of Excellence charged with combining workers’ protection and their health promotion into single programs. The term Total Worker Health®, trademarked by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, refers to the synergistic combination of health promotion and worker safety.

The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), through its fire prevention and safety grants, supports research to reduce firefighter injuries and improve their safety, health and well-being. Assisting wildland firefighters is one of FEMA’s research priorities. FEMA notes in its funding announcement that “the physical demands and fire environment, as well as the tactics and equipment associated with wildland fire fighting differ from structural fire fighting. Research directed at mitigating the safety and health hazards associated with wildland fire fighting is encouraged.”

We set our sights on designing a safety and health program for wildland firefighters, and in 2019 we were funded by FEMA to do just that. However, addressing the needs of wildland firefighters had unique challenges, and we looked to wildland firefighters to help us accomplish the task.

An obvious challenge is the increase in the size and number of wildland fires. Fire seasons are longer, with more and larger fires placing increased demands and risks on all those fighting wildland fires. A second factor is the many different types of individuals fighting wildland fires. In the United States, there are about 15,000 federal full-time and seasonal employees; 400,000 career structural firefighters involved in wildland urban interface (WUI) fires and deployed to fire camps; and 800,000 volunteer firefighters who comprise the majority of those protecting smaller, rural communities. Third was the need to have an engaging and effective program applicable in all the different settings of this busy, often exhausted, workforce.

For the content of the program, we reviewed the literature on the adverse effects of wildland fire fighting and consulted experts in smoke exposure, nutrition, cancer risk and other topics. Studies of the health effect of wildland fires is growing but is much less than structural firefighting. For example, the leading search engine listed more than 500 publications in 2021 for structural firefighting, and less than 30 for wildland fires. Importantly, we conducted individual and group interviews with more than 150 wildland firefighters from sites across the United States, as well as those involved in training and certifying wildland firefighters.

Those interviews were used to prioritize content for the program. We had intended to visit sites to conduct the interviews in person. However, after visits to sites in Oregon, Idaho and Montana, Covid shut that down. While we missed getting to see training facilities and shake the hands of these hardworking individuals, we successfully re-tooled to finish the work through virtual meeting interviews.

During the recorded interviews, we asked participants to tell us about the needs of wildland firefighters. To bring science to analyze findings from the interviews, we read the transcripts and tallied the comments made in specific topic areas. The highest number of comments related to mental health, followed closely by fitness and physical demands. Nutrition and fatigue issues were frequently mentioned. Surprisingly, risks for heart disease and cancer were rarely mentioned, despite the heightened risk for both among wildland firefighters. The findings identified safety and health needs and informed the program’s content. For heart disease and cancer, we needed to include facts about why those are relevant and their potential long-term adverse consequences, as well as how those health risks could be mitigated. The final list of session topics is in Table 1. Six are the core topics, recommended for all those fighting wildland fires, with additional electives, including more information on mental health, fitness and nutrition. To underscore that, the program is designed “by wildland firefighters for wildland firefighters” their de-identified interview quotes were incorporated into each session.

Once we had the content, we needed a delivery format that would be versatile enough to be used by an individual, as a group, or in a training setting facilitated by an instructor. We wanted the program to be a fit during preseason training, when stationed at a fire camp, by station-based career structural firefighters and during training sessions of rural, mainly volunteer fire departments.

Wildland firefighters helped us determine how to deliver the content too. During the interviews we asked how wildland firefighters liked to learn and what training activities were most effective. Like most adult learners, the interviewees wanted activities that were engaging, relevant and provided explicit advice; they preferred bite-sized content that could be easily accomplished in limited time. Accordingly, we designed a series of 30-minute sessions that could be accessed on a computer, tablet, or smartphone. We built the program using Articulate 360, which is a well-established platform for e-learning course development; it includes access to hundreds of prebuilt games, reveals, and many other interactive features that can be modified for specific content. The program allows the addition of short videos and has thousands of stock photos that can be used.

Building a session was an iterative process of working and re-working the content. For each session, we started with an outline: What information and new facts did we want to present? What safety and health behaviors did we want to promote? We needed to translate those objectives into effective, fun activities using Articulate. As a result, each of the sessions contains approximate 20 different images or wireframes. The wireframes provide the baseline structure to which the interactive features (e.g., games, reveals, videos and links to other content) can be attached. Wireframes from the initial component of the program, including acknowledgement of our partnering organizations, are shown in Figure 3

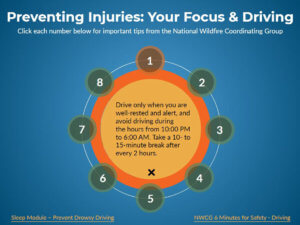

Our team worked on each session until we determined that the session achieved its objectives. When we had a near-final product, we asked local wildland firefighters to review the session and tell us what they were thinking while they worked through the content. This “think aloud” method is an accepted means to evaluate product usability. For example, we had a component during which firefighters were asked to type in answers, but the reviewers indicated that firefighters would likely skip over this section, and the activities needed to be more gamified with choices and buttons to maintain engagement. Videos longer than a couple of minutes generally did not hold reviewers’ interest, and sessions were structured to keep participants engaged with the material throughout the sessions. We included links to additional resources, and the reviewers liked the fact that the sessions were lean and provided the ability to click on links to learn more about topics of interest. Examples of one wireframe from the sessions on Hydration & Heat Injury, Nutrition and Injury Prevention are shown in Figure 4. Those pictures do not capture the dynamic and interactive aspects of the program, and they are only a single image from among the more than 20 wireframes in each session.

Each session follows a similar format. First, firefighters process the facts, new information and behaviors needed to improve safety and health related to the session’s topic. Each section ends with a “Bottom Line,” of the critical actions needed for safety or health, and firefighters are asked to identify personal opportunities to improve their safety and health. The next session begins with follow up on the prior session’s objectives. We know safety and health promotion is a process, and the program is designed to support and reinforce healthy actions. Our group has repeatedly demonstrated that this structure results in improved understanding and positive actions across different contents and learner groups from high school athletes to homecare workers, truckers, and structural firefighters.

To call the program evidence-based, we need to demonstrate that it works when used by individuals fighting wildland fires. We are in the final year of this three-year project and completing data collection on more than 100 firefighters across the United States who have used the program. Early pre- and post-survey findings indicate significant positive outcomes. Initial results of selected post-survey items are shown in Table 2, and examples of the many positive quotes from program users are included in Table 3. When data collection is completed, we will share those findings and importantly, use the feedback from to fine tune the program before making it freely available for all those fighting wildland fires.

Later this year, we will work with the National Fallen Firefighter Foundation (NFFF) and First Responder Center for Excellence for Reducing Occupational Illness, Injuries and Deaths, Inc. (FRCE) to develop the program for the NFFF website. We appreciate the NFFF’s and FRCE’s partnership in disseminating the program, as well as all the many firefighters who helped with program development and assessment. When we worked with career structural firefighters our tagline was protecting the safety and health of those protecting us; with this project we extend that to those protecting us and our environment.

Table 1

Topics for the program’s 30-minute, six core and eight elective sessions

| Core 1 | Heart Health |

| Core 2 | Hydration & Heat Injury |

| Core 3 | Physical Fitness |

| Core 4 | Nutrition on the Line |

| Core 5 | Sleep & Fatigue |

| Core 6 | Mental Fitness |

| Elective | Advanced Mental Fitness |

| Elective | Alcohol Science |

| Elective | Cancer Prevention |

| Elective | Effective Leadership |

| Elective | Injury Prevention & Treatment |

| Elective | Medical Check-up |

| Elective | Nutrition Off the Line |

| Elective | Supplements: Help or Hype |

Table 3

Examples of written comments submitted by those completing the program.

| Table 3. Sample wildland firefighter feedback |

|

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Diane Elliot, MD, is a professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University. She has worked to develop and disseminate evidence-based safety and health programs for several groups. Including high school athletes, younger workers, homecare workers, and structural firefighters.

Diane Elliot, MD, is a professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University. She has worked to develop and disseminate evidence-based safety and health programs for several groups. Including high school athletes, younger workers, homecare workers, and structural firefighters.

Susanna Ek is a former emergency medicine technician and the research assistant responsible for coordinating this project.

Susanna Ek is a former emergency medicine technician and the research assistant responsible for coordinating this project.

Kerry Kuehl, MD, DrPH, MS is a professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University and chief of Health Promotion & Sports Medicine. He is the principal investigator on this project. Dr. Kuehl has a long history of working with first responders, including law enforcement and the fire service to improve their safety and health.

Kerry Kuehl, MD, DrPH, MS is a professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University and chief of Health Promotion & Sports Medicine. He is the principal investigator on this project. Dr. Kuehl has a long history of working with first responders, including law enforcement and the fire service to improve their safety and health.

Acknowledgements: Our team at Oregon Health & Science University has worked tirelessly on this project including Jessica Ballin, MPH; Carol DeFrancesco, MFA, RD; Wendy McGinnis, MS; and Adrienne Zell, PhD.