Coping Skills for Overwhelm

BY BEQUI LIVINGSTON

Have you ever found yourself on the fireline, feeling overwhelmed? Or maybe you felt fully in control, hyped up with adrenaline. Your body and brain may not have been in alignment, but you charged on. Perhaps you’ve felt angry, or as if you wanted to run away, or your brain was foggy, or even a bit lethargic and physically unable to keep up. Do any of these scenarios sound familiar? Now, recall a traumatic fire event in which you were involved; how did you respond?

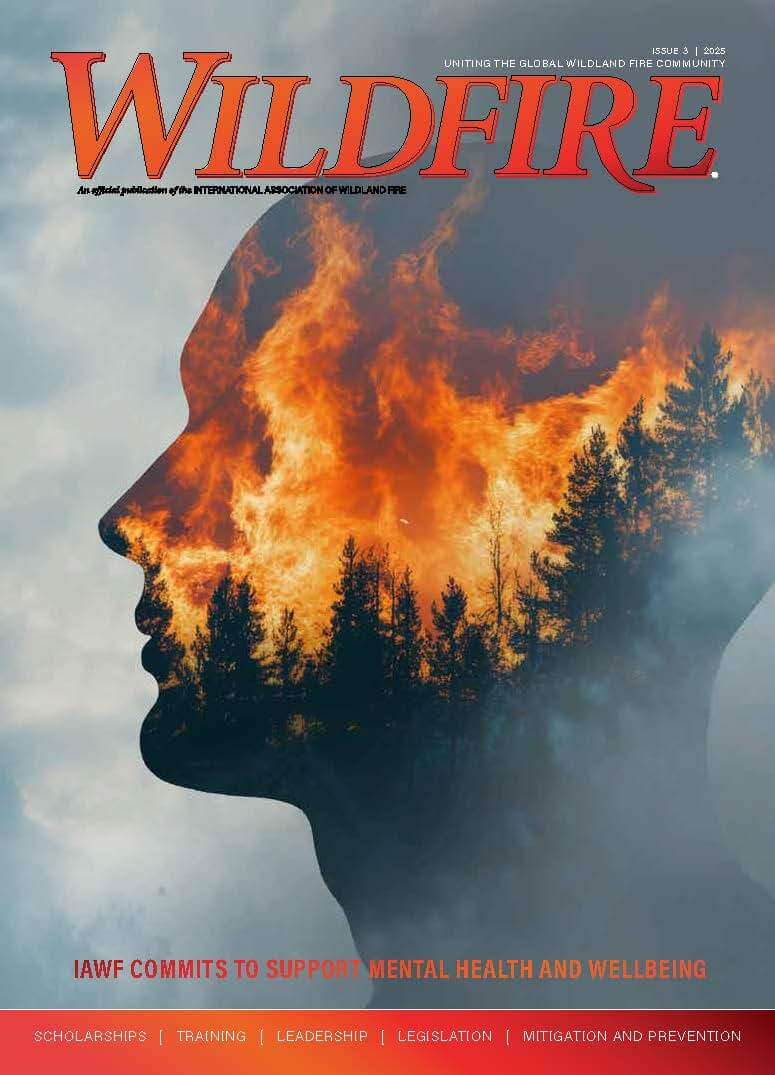

I’ve written a lot about the autonomic nervous system and the importance of understanding its involvement in wildland fire. Just being a wildland firefighter puts people at a higher risk for nervous system overwhelm and dysregulation, especially with the unprecedented wildland fire seasons we’re experiencing. That’s why it’s important to understand your default state of survival, and how best to mitigate and manage when your autonomic nervous system gets overwhelmed. Understanding how you respond under duress and when you’re overwhelmed can be essential to your health and wellness, and especially to your safety on the fireline.

I remember the 1982 fire season; I was assigned to a wildfire in the Capitan Mountains in New Mexico. It was a lightning fire and several members of the Smokey Bear Hotshot crew and the Capitan Helitack crew I was on were flown into the fire. We had dug fireline for most of the day, finally bedding down about 2200 hours. We had only our sleeping bags, and I was the only female.

As usual, I could not go right to sleep. Somehow, I had convinced myself that a bear was going to come into our sleeping area because we had seen fresh bear scat. About midnight, I started hearing bushes rattling and twigs breaking and was convinced that the bear was coming to get me.

I lay in my sleeping bag, frozen in fear. Then came the growls; they seemed to get closer and louder, and I lay frozen. I started whispering to my crew mates, “Dan, is that you, do you hear that?” Nothing. Then, “Brian, do you hear that?” I went around to several others but there were no replies. After about 30 minutes, the growls subsided, but I still lay awake, my heart beating, my palms sweaty. The next morning it became apparent that the growling had been one of the crewmembers snoring loudly. I had been frozen in the survival response of hypoarousal or dorsal vagal parasympathetic shutdown; my nervous system was trying to keep me safe and out of harm’s way.

When we’re stable and not dealing with the chaos and trauma of wildfire, our autonomic nervous system falls into a normal range within our window of tolerance. The window of tolerance refers to the optimal zone of emotional and physiological arousal when a person can function effectively while managing stress; it’s where we feel functional, clarity, safety, stability, grounded, and able to make decisions. If you were to use a stoplight as an analogy, the window of tolerance would be green; it’s the place we want to practice being, where we feel that we can deal with the chaos and bounce back from adversity. When trauma and stress shrink your window of tolerance, it doesn’t take much to throw you off balance, to become overwhelmed and dysregulated. Everyone’s window of tolerance is different, and factors that can affect it include past trauma, neurobiology, and social support.

When we are stressed or overwhelmed, our window of tolerance shrinks, activating the sympathetic survival mode, referred to as hyperarousal, or red, meaning STOP; we feel activated, triggered, want to fight or flee. Red is where we are so activated or anxious that we can’t make rational decisions because our prefrontal cortex (cognitive brain) has gone offline. Red is a place of anxiety, hyperarousal, hypersensitivity, and overwhelm. Our stress hormones are in overdrive, and our system wants to keep us safe. Yet, this state can be detrimental and unsafe in a fire situation.

Then there’s the parasympathetic dorsal vagal survival mode, also known as hypoarousal, where we tend to freeze, shut down and collapse, often unable to move or speak, and a dangerous place to be in a fast-moving wildfire. Hypoarousal is where you might feel spaced out and even numb; it’s often where depression occurs because our nervous system is trying to slow down to keep us safe.

These reactions are not something we choose, they just take over, leaving us little control, other than learning to manage and mitigate their effects. Once you begin to pay attention, being mindful of how you respond to trauma and stress, you will be better able to handle different nervous system states. Awareness is the first step. Step two would be paying attention to where you feel these responses in your body. What does anger feel like in your body, and where do you feel it? What does flight mode feel in your body and where is it located? What about freeze and shut down? Where do you notice it in your body?

Once we begin to recognize our unique survival default state, we can work with our nervous system, helping it become stronger and more resilient for when danger happens. The nervous system becomes your personal warning system. Most importantly, you want to begin practicing coping techniques and tools before you are dealing with chaos; doing so makes it easier to defer to the skills when your body and brain are in survival mode. Everyone’s coping skills and tools will be different, so please find what works for you and throw out the rest.

Over time we can refine coping skills to better help us deal with the overwhelm. Tools include the following:

HYPOAROUSAL AND OVERWHELM

When you are activated in fight-flight and your system is overwhelmed, you want to slow and calm things.

• Grounding and anchoring; Practice using your senses:

• Feel your feet make contact with the ground, maybe your back being supported and your behind in a seat. Focus your attention on the sensation of touch.

• Notice what you see, hear, taste, smell and touch – colors, shapes or textures; feel your clothes on your skin.

• Breath work is one of the quickest and best ways to calm an overwhelmed nervous system. Start by noticing your breath without trying to change it. Then, try one of these:

• Calming breaths: Inhale slowly through your nose, pause at the top and then exhale out your mouth with a sigh, letting it all go. Repeat three to four times then come back to your normal breath.

• Box breathing: Inhale through your nose to the count of four; pause at the top for four; exhale through the nose for four; and pause at the bottom for four, as if you’re drawing a box with your breath. Repeat three to four times and come back to your normal breathing.

• 4-7-8 breathing: Inhale slowly through your nose for four counts, hold and pause for seven counts, then slowly exhale through your mouth, as if you’re breathing out through a straw for eight counts. Repeat three to four times and come back to your normal breathing. (If you must abbreviate to a lower count, such as 3-6-7, that’s fine.)

• Mantra / intention: Saying to yourself, “I am here now, and I am safe.”

• Mindfulness: Becoming fully present with everything you are experiencing, even when it’s uncomfortable to do so. If your thoughts distract you, bring your focus back to your breath, and feel your body become anchored and grounded. Returning back to the breath and body, over and over again, will help keep you present in the moment.

HYPERAROUSAL, FREEZE AND SHUTDOWN

When you feel frozen in place, as if you can’t move, can’t breathe or make a decision, you need to activate your nervous system.

• Splash cold water on your face, plunge your head into cold water, or hold on to a cold object such as a cold can or piece of ice.

• Move your body; do some jumping jacks, push-ups or walk quickly to get your blood flowing and your body engaged.

Grounding and anchoring practices

• Feel your feet make contact with the ground, maybe your back being supported and your behind in a seat. Focus your attention on the sensation of touch.

• Notice what you see, hear, taste, smell and touch –colors, shapes or textures; feel your clothes on your skin.

• Breathwork: use any of the breathing exercises mentioned above.

• Mindfulness: become fully aware of your nervous system state and practice tools to re-activate it.

• Healing touch or self-soothing practices:

• Butterfly hug: put opposite hands on your shoulders, as if you’re hugging yourself and begin gently tapping, alternating between right and left.

• Self-havening: slowly rub your hand down your arms and wring your hands slowly.

• Mindful movement: walk slowly; place each foot in front of the other and pay attention to how it feels.

• Mantra or intention: Kind words you need to hear, that you can tell yourself, for example, “I am safe in this moment and doing the best I can.”

Other body-based / somatic coping skills and tools:

• Massage

• Chiropractic

• Cranio-sacral massage: a gentle hands-on massage that helps release tension in the craniosacral region, which includes the skull, spine and sacrum, helping move the cerebral fluid through the spine, helping to calm the nervous system.

• Acupuncture

• Yoga/ Tai Chi / Qigong

Brain-based coping skills:

• Neurofeedback: a type of therapy that teaches clients how to regulate their brainwave activity, potentially helping reduce symptoms related to nervous system overwhelm and other conditions.

• Trauma-informed therapy (personal and group)

• Psychoeducation: Learn everything you can about the nervous system, especially as it relates to first responders.

• Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (by a highly trained EMDR therapist).

There are many other tools; only you can find the techniques that work best for you.

Bequi Livingston was the first woman recruited by the New Mexico-based Smokey Bear Hotshots for its elite wildland firefighting crew. Livingston was the regional wildfire operations health and safety specialist for the U.S. Forest Service in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Contact her at [email protected]

Bequi Livingston was the first woman recruited by the New Mexico-based Smokey Bear Hotshots for its elite wildland firefighting crew. Livingston was the regional wildfire operations health and safety specialist for the U.S. Forest Service in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Contact her at [email protected]