AFTER THE FIRE

HOW POST-INCIDENT STUDIES BRING INSIGHTS TO WUI SCIENCE

BY BENJAMIN GAUDET, STEVEN GWYNE, ERICA KULIGOWSKI, NOUREDDIE BENICHOU AND ALBERT SIMEONI

Understanding the short- and long-term effects of a fire on people and the community, understanding patterns of life and property loss, determining the pathways of fire spread, and improving fire safety codes and standards are examples of the goals of WUI fire post-incident studies.

The complexity and scale of wildfires makes them difficult to counter or to study, both in real-time and afterwards.

However, the increasing severity of wildfires around the world has brought additional focus on the study of their interaction with the urban interface.

The most direct way to study a wildland urban interface fire, short of collecting information during the event itself, is a post-incident study; this type of study involves assembling and deploying a group of researchers to the fire location to collect information from a variety of sources immediately after the fire.

Organizations such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the United States and the former Bushfire and Natural Hazards Cooperative Research Center (BNHCRC), now the Natural Hazards Research Australia (NHRA), have conducted post-incident studies – typically in collaboration with local authorities – for WUI fires and other natural hazards including tornadoes and hurricanes.

To date, NIST has studied four WUI fires since 2007, including the Camp Fire in California in 2018, which remains the deadliest wildfire in California history.

The seminal studies conducted by the BNHCRC involved the Black Saturday bushfires of 2009 and the more recent 2019-2020 Black Summer fires, among others.

In Canada, a post-incident study of the 2016 Fort McMurray fire was used to assess causes and effects of Canada’s costliest disaster to date.

Post-incident studies provide a means to extract information pertaining to fire dynamics, fire spread within the built environment, and the human impact and response; this information can then be used to inform firefighting tactics, evacuation protocols, building codes, and education of residents in areas of high fire risk.

IMPLEMENTING A POST-INCIDENT STUDY FOR A WUI FIRE

Since 2013, California alone has endured no less than 6,950 individual wildfires each year. Similarly, Canadian wildfires have numbered on average 6,000 per year over the past decade. The 2019-2020 fire season in Australia resulted in an area burned almost the size of Syria (72,000 square miles).

As wildfires have grown in intensity and size, a greater number of communities at the wildland interface have been affected. Since all fire events cannot practically be studied, specific ones must be selected to gain key insights. A decision to select and study a fire event balances the cost of allocating resources to that study with the potential of fulfilling research goals and answering meaningful questions that advance understanding of WUI fires. Understanding the short- and long-term effects of a fire on people and the community, understanding patterns of life and property loss, determining the pathways of fire spread, and improving fire safety codes and standards are examples of the goals of WUI fire post-incident studies. Researchers ask whether the fire being considered for a post-incident study can produce data that fills knowledge gaps related to these goals and, more broadly, the fire dynamics and human impact of WUI fires.

To obtain the reliable information needed to answer this question, researchers seek information from incident authorities who oversee the emergency response and recovery efforts, or researchers conduct reconnaissance trips to the fire location immediately after the fire. The incident authorities may represent levels from local to federal and are responsible for responding to and managing fire events. Examples of major WUI fire incident authorities in the United States are the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CALFIRE). The Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (CIFFC) organizes and coordinates responses to wildfires across multiple incident authorities. In Australia, fire service organizations on the state level, such as Country Fire Authority and the Department of Environment, Land, Water, and Planning in the state of Victoria, act as incident authorities for bushfires within their jurisdiction.

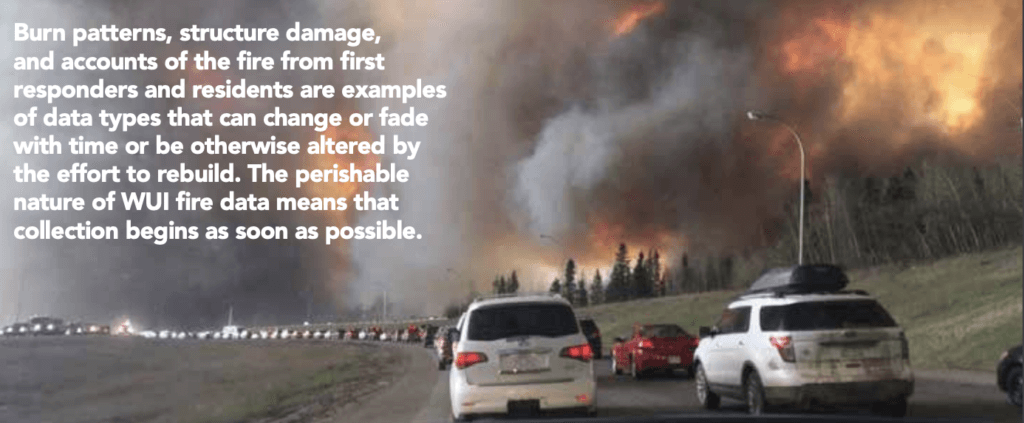

While wildfires can require days or weeks to be fully contained, their spread through a community can happen in a matter of hours. Similarly, the data on WUI fire impacts on a town or populated area are perishable in that they can be altered, destroyed, or forgotten in the days after the fire. Burn patterns, structure damage, and accounts of the fire from first responders and residents are examples of data types that can change or fade with time or be otherwise altered by the effort to rebuild. The perishable nature of WUI fire data means that collection begins as soon as possible. Hence, post-incident studies are often also referred to as rapid-response studies. Equally as important, the effort of researchers to study the fire cannot interfere with those overseeing emergency response to the fire, including local police and fire departments, state or provincial authorities, or other incident command entities. In fact, all post-incident studies conducted by both NIST and the BNHCRC involved collaboration between incident authorities and the researchers.

INFORMATION COLLECTED

The scale and scope of information needed to meet research goals and to draw meaningful conclusions from a WUI fire can require weeks or months of data collection. Dozens of data types from thousands of individual sources can be included in an analysis.

Post-incident studies generally collect information in five major areas:

- Fire event timeline

- Local weather, topography, and wildland environment

- Response of the structures and land parcels to fire

- Emergency response actions

- Human and community response to the fire.

A fire event timeline is how the fire progressed in both space and time and is the foundation for bringing the entire event into context. A completed timeline describes the path of fire movement from its origin in the wildlands to its spread to communities and structures, as well as its spread from structure to structure. Fire damage patterns among structures and vegetation, the local topography, first responder radio logs, time stamped videos and photos, automatic vehicle location (AVL) logs – which contain GPS tracker data of first responder vehicles, 911 call records, and a variety of other data sources are used to piece together an image of where, when and how the fire spread. Interviews with first responders, residents or other eyewitnesses are also critical sources of information.

Local weather, wildland vegetation and environmental information give context to fire spread and fire severity. For instance, hotter, drier conditions – especially periods of prolonged drought – are conducive to fire ignition and spread. Fires spread more quickly among dry, dense vegetation and while moving uphill as opposed to downhill. Fire severity is also linked to how much time has passed since a prior fire in the same area. Terrain and elevation maps, fire history maps, aerial imagery of the community layout and wildland fuel maps can be used to indicate why certain areas of the community may have been more heavily impacted than others.

The response of structures and land parcels is studied to understand fire spread pathways, fire spread vulnerabilities and the effectiveness of fire mitigation measures. Mitigation measures include fuel load management, fire-resistant construction, and control of fire spread pathways. Using fire-resistant siding and roofing materials, reducing the presence of combustible vegetation directly next to a home, or keeping a roof free of dry debris are examples of mitigation measures.

The assessment of fire damage to structures and land parcels is also done in the context of defensive actions. First responders protecting a home is an example of a defensive action that can be the difference between one home being destroyed and another emerging unscathed, regardless of the presence of other passive fire protection measures or risk factors. Defensive actions also tie back to understanding the emergency response to the fire. First responder tactics and a timeline of first responder actions add context to where and why fire damage is present.

Interviews with fire survivors and emergency responders are often collected to better understand a community’s response to a fire event. At the household level, questions are often posed to survivors about their demographics, knowledge and experience with fire, the cues and warnings that they received during the event, their threat and risk perceptions, and how they protected themselves. By understanding what people did and why (for example, why some people evacuated and others did not), potential areas of improvement to public education and preparedness as well as community planning can be identified. Also of interest is the role that official evacuation warnings and orders played in the public’s response to the fire. Assessing evacuation messages for their content and dissemination methods can shed light on why the public may have responded in certain ways during the fire.

THE OUTCOME

Post-incident studies are a powerful tool for collecting direct information about a wildfire. In general, the information from WUI fire post-incident studies can be used to improve evacuation and emergency response practices, anticipate and mitigate the pathways of fire spread within a WUI community and improve the fire resilience of at-risk communities in advance of future fires. The information from post-incident studies can also contribute to legislative code requirements. The impacts of advancing understanding of WUI fire disasters can be seen in the implementation and continual improvement of community resilience programs such as Firewise USATM in the United States or FireSmartTM in Canada. However, much progress can still be made. The purpose of post-incident studies in the world of WUI fire science is to provide fundamental knowledge to fuel this progress.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Benjamin Gaudet is a fire protection research and development engineer working for UL LLC outside of Chicago, IL. He graduated from WPI with a Masters degree in fire protection engineering.

Benjamin Gaudet is a fire protection research and development engineer working for UL LLC outside of Chicago, IL. He graduated from WPI with a Masters degree in fire protection engineering.

Dr. Steve Gwynne is research lead at Movement Strategies (a GHD company) and industrial professor of evacuation and pedestrian dynamics at Lund University, Sweden. He has nearly 25 years of experience in pedestrian dynamics, human behaviour in fire and evacuation modelling.

Dr. Steve Gwynne is research lead at Movement Strategies (a GHD company) and industrial professor of evacuation and pedestrian dynamics at Lund University, Sweden. He has nearly 25 years of experience in pedestrian dynamics, human behaviour in fire and evacuation modelling.

Erica Kuligowski is a social research scientist who studies human behavior during emergencies and the performance of evacuation models in disasters. She is a Vice-Chancellor’s Senior Research Fellow in the School of Engineering at RMIT University in Australia, studying evacuation and emergency communications during bushfire, building fires, and other hazards.

Erica Kuligowski is a social research scientist who studies human behavior during emergencies and the performance of evacuation models in disasters. She is a Vice-Chancellor’s Senior Research Fellow in the School of Engineering at RMIT University in Australia, studying evacuation and emergency communications during bushfire, building fires, and other hazards.

Noureddie Benichou is principal research officer within the Fire Safety Group at the Natioal Research Council of Canada. HIs research includes modeling and experimentation of fire resistance of structures, fire safety in buildings, fire risk analysis, and the impact of wildfires on the wildland urban interface.

Noureddie Benichou is principal research officer within the Fire Safety Group at the Natioal Research Council of Canada. HIs research includes modeling and experimentation of fire resistance of structures, fire safety in buildings, fire risk analysis, and the impact of wildfires on the wildland urban interface.

Albert Simeoni is a professor and department head, Department of Fire Protection Engineering, at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute. He is an expert in fire dynamics and fire impact, with a main focus on wildland and wildland-urban interface fires.

Albert Simeoni is a professor and department head, Department of Fire Protection Engineering, at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute. He is an expert in fire dynamics and fire impact, with a main focus on wildland and wildland-urban interface fires.